Flaka Haliti

:

Manufactured For the Purpose of Fainting (After Screaming)

Back

Information

It was predominately female bodies that told this story and have passed it on many times since. They continue to tell it over and over again, inventing wondrous details—like globus hystericus, in which the poor imprisoned voice pleads to be released. And they do not proclaim their stories with words, but with bodily images and physical signs.(1)

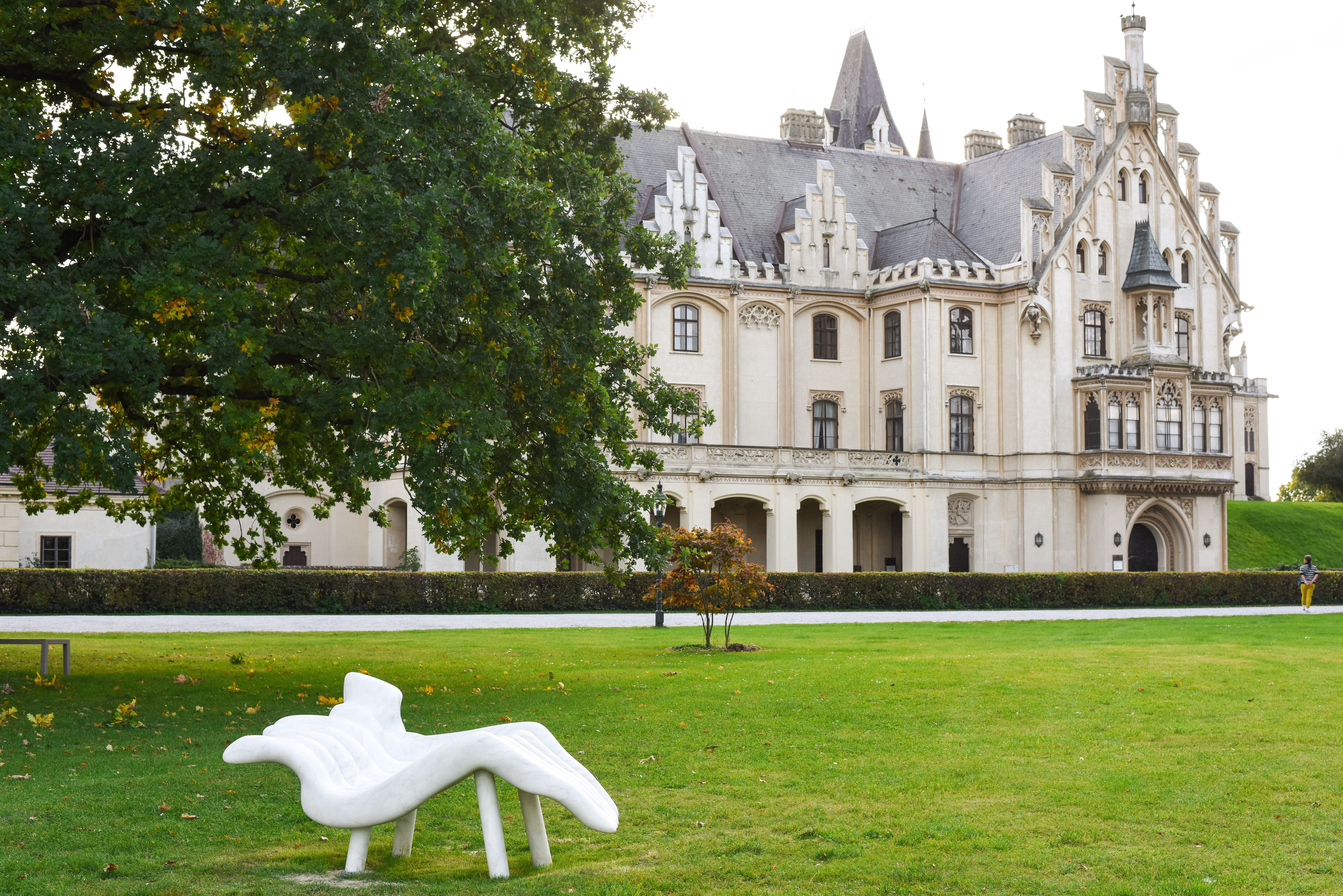

Flaka Haliti found the perfect place for her sculpture, and the sculpture found its perfect place. Her piece of furniture for sitting made of white marble is located in a romantic English landscape garden. The garden surrounds a castle that has been remodeled in the neo-Gothic Tudor style of the 19th century and whose structure dates back to mediaeval times. Not only were theater plays performed in the park during the Baroque era, since an impressive architectural and sculptural outdoor pavilion Wolkenturm (Cloud Tower) was constructed in 2007, music events are also held there.(2) Grafenegg is therefore a theatrical and performative place, crisscrossed by history and stories that are permanently played out in nature, in architecture, and in music in a multifaceted way.

Haliti’s Manufactured for the Purpose of Fainting (After Screaming) refers to a notorious piece of 19th century furniture—namely, the chaise longue—a mythical object, which (in retrospect) became known as a “fainting couch.”(3) Its analytical counterpoint was another equally mythical piece of furniture from the end of the 19th century: the couch in Sigmund Freud’s office.(4) The “fainting couch” got its name from the allegedly hysterical fainting fits of women who, after screaming, would sink onto this object, which is a hybrid of an armchair and a bed. More than just a passing fad among well-to-do women at the time, hysteria was talked up as the female illness of the century and was used to discriminate against women. In retrospect, it was likely a (pathologized) medium for expressing a collective modernist experience—in other words, universal rationalization and mechanization, and not least the advancement of visual media. Thus, Jean-Martin Charcot, who described himself as the “inventor of hysteria,” took photographs of his female patients, staging them in a performative setting that included both sides of the phantasm to an equal degree: the “technicians” representing the apparatus of the male gaze on the one hand; and the women systematically photographed in poses or “attitudes passionelles” (Charcot) on the other.(5) However, it was Sigmund Freud who first attempted to express the complex history of those suffering from hysteria (women or men) in his attempt to reveal the origins of their physical symptoms.

Moving this discussion into the present day, Haliti asks the tongue in cheek question: “Was it the corset, the arsenic, or mannerism—as then? Or was it the hangover, the confusion or the stress—as now? Why did I really faint last time?”(6) Haliti’s choice of material for her “fainting couch” also refers to another myth that has since lost its appeal: White marble, which symbolized the “nobility” and “purity” of antiquity in the Classicist era of the 18th and 19th century, becomes a kind of subtle counter-fantasy to the middle-class notion of the “abject” female hysteric. The same subversive humor found in the title Manufactured for the Purpose of Fainting (After Screaming) can thus also be detected in the sculpture. Her “fainting couch” is a cross between a piece of furniture and the human body, between seemingly soft cushions and hard stone, between an animistic flair and a pose frozen in marble—the “imprisoned” voice included. Haliti manages to capture the specific moment of the fabrication of the hysteria phantasm and the erotic seduction associated with it. The illusionism conjured up by her couch sculpture refers not only its nature as an eye-catching object, which from afar looks like a strange animal from a magic garden, but also its material and tactile qualities, and its elegant form, with its almost fetishistic shiny and smooth surface. While the fainting couch is not really meant for us to faint on, it is well suited for a comfortable rest—or for philosophizing, as once was the practice in antiquity, and which Flaka Haliti refers to as well.(7) Regardless, Manufactured for the Purpose of Fainting (After Screaming) is sure to remain a popular attraction for picture-taking, with or without someone posing for the camera.

Silvia Eiblmayr

Notes

1 Christina von Braun, “Die Stimme der Diva,” in Die verletzte Diva. Hysterie, Körper, Technik in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts, ed. Silvia Eiblmayr, Dirk Snauwaert, Ulrich Wilmes, and Matthias Winzen (Cologne: Oktagon, 2000), 97.

2 The Wolkenturm (Cloud Tower) was constructed in 2007 in the park, east of the castle. It is an open-air stage with 1,700 seats and room for 300 people on the lawn. It was created by the next ENTERprise (Marie-Therese Harnoncourt & Ernst J. Fuchs) and the landscape architects of Land in Sicht. The sculpture-like construction resembles the amphitheaters of Baroque gardens, while also alluding to formal elements of other existing structures in the park. See https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schloss_Grafenegg (accessed October 26, 2020).

3 See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fainting_couch (accessed October 26, 2020).

4 Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) received the couch as a present from a female patient in 1890. It was one of the belongings Freud was able to take with him when he fled from the Nazis to London. It is now in the Freud Museum in London. See https://www.freud.org.uk/collections/objects/4380/ (accessed October 26, 2020).

5 See Georges Didi-Huberman, Invention of Hysteria. Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière, trans. Alisa Hartz (Cambridge, MA/London: MIT Press, 2003).

6 Flaka Haliti, Manufactured for the Purpose of Fainting (After Screaming): text for the project for Grafenegg, 2019, unpublished.

7 Ibid.

Images (4)