100 JAHRE FRAUENWAHLRECHT

BackArtists

- With

Information

HISTORY THAT MOVES US ALL

“We do not blindly seek suffrage, but are fully aware that the right to vote means power.” (Marianne Hainisch, commemorative publication of the Austrian Women’s Suffrage Committee, Vienna 1913)

2018 is a very important anniversary year for many decisive events in the history of Austria and Europe. We are commemorating and remembering the founding of the First Austrian Republic in 1918, the Revolution of 1848, the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938, and the student protests in 1968. It is also an occasion to renegotiate our culture of remembrance and remembering, which is why it is especially important to give due regard to yet another anniversary that has played a role in our democracy: The introduction of the women’s right to vote in Austria in 1918. Although there is no gap in our historical consciousness about this event—its history has been intensely and comprehensively researched—the first women’s movement and its relevance for our society nevertheless do not seem very deeply rooted in our collective memory, and it does not seem to play a role in the broader public discourse today. At the initiative of the Women's Department of the Office of the Provincial Government of Lower Austria, the Department of Art and Culture/Public Art Lower Austria decided to use this occasion to honor this milestone of our history by developing a temporary, multipartite public art project with the goal of reminding the general public of the 100-year anniversary of women’s suffrage and the history of the suffragettes through art. An expert jury therefore invited several women artists to participate in the project: Jakob Lena Knebl, Isa Rosenberger, and Susanne Schuda designed posters, while Susi Jirkuff created animated films.

A Long Struggle

November 12, 1918, saw the introduction of the “general, equal, direct, and secret right to vote for all citizens, regardless of their gender.” For the first time in history, Austrian women were allowed to vote and to run for office in the national election on February 16, 1919, on equal footing with men. Eight women were elected into the National Assembly. Although the introduction of the right to vote for women ultimately had its roots in the political, economic, and social changes in the aftermath of World War I, the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the founding of the Austrian Republic, it was also the product of many working and middle-class liberal movements that fought for, and finally achieved, the political participation of women all over the world.

In Austria, the struggle was born out of the March Revolution of 1848, when women demonstrated for equal pay for the first time—some of them even losing their lives in the process. When that revolution was crushed, a neo-absolutist system was installed, delivering a horrible blow not only for democracy, but also for women and their struggle for equal rights, and they were excluded from public life to an even greater extent than before. At the turn of the 20th century, women were still regarded as second-class citizens, because they were completely economically and politically dependent on their families and/or husbands and could not stand up for themselves on the political stage.

The Austrian suffragettes knew that political participation was a privilege of the wealthy and educated, which is why they concentrated on improving education for women. Females were not only excluded from political activities and membership in clubs and associations, they were also not allowed to pursue higher education or study at colleges and universities. The first secondary school for girls was established in 1892 thanks to Marianne Hainisch, a key figure of the middle-class, liberal women’s movement who also founded the federation of Austrian women’s associations in 1901.

As the situation began to change slowly after the turn of the century, women’s suffrage finally grew in importance in the eyes of the public, not least due to the countless initiatives, petitions, resolutions, and demonstrations of the independent women’s suffrage committees in Vienna, Prague, and Brno that were founded in 1905. Women’s suffrage in Austria, which was introduced at the same time as the declaration of the First Austrian Republic in 1918, not only ended the exclusion of women from political decisions; it also reflected the socio-political reality that could no longer be ignored after World War I, which is that women have always been part of public and social life and have always made a significant contribution to the country’s economy.

There Is Still Much To Be Done

Today, we tend to take women’s rights for granted. Yet, the introduction of the women’s right to vote was only the first in many social and political steps toward ensuring gender equality. Even now, 100 years later, there still is structural discrimination against women, male power structures continue to exist, and women and men still do not enjoy the same opportunities. We need many more organized efforts to meet all of the original suffragettes’ demands. We only have to think of the significant income gap, the fact that childcare and the care of relatives is for the most part still done by women, or that women are still facing blatant sexism today. Significantly less women than men also hold a political office still today, and it is a simple fact that the Austrian parliamentary system continues to be dominated by men in 2018. The ratio of women in parliament is only roughly 34 percent, while merely 7.6 percent of Austria’s towns and cities are run by a female mayor, and Lower Austria is only the third Austrian state to have a woman governor.

Against Historical Amnesia

The four artists Susi Jirkuff, Jakob Lena Knebl, Isa Rosenberger, and Susanne Schuda all chose different approaches to this theme, yet all combine the historical development of women’s political participation with contemporary aspects. The public and digital realm serves as a projection surface and multiplier for their posters and films. The goal of the project is to achieve the greatest possible visibility for this important issue and to initiate an ongoing engagement with it. The artistic contributions encourage us to look closer, to ask critical questions, and to become actively involved at the intersections between private and political, between the personal sphere and the existing social reality. In its power to interact with the audience, art has the potential to establish a public platform through which complex historical parallels can be explored and applied to our present time.

Another major goal of this project is to reach young people and to raise their awareness of the pioneering achievements of women, thereby rooting these more firmly in our collective memory and counteracting wide-spread historical amnesia. Especially with the raised awareness from the #MeToo debate, now more than ever we need to address problems openly and to sensitize younger generations about this issue. The free brochure accompanying the project will therefore be distributed not only at a variety of institutions, but also especially at schools. The artists also conceived workshops for older high-school students and for art teachers that allow them to delve deeper into this issue using specific approaches, inspiring a direct dialogue.

The artists’ posters are on display in Lower Austria between October and December, and the video project can be viewed online.

(Georgia Holz)

Contributions

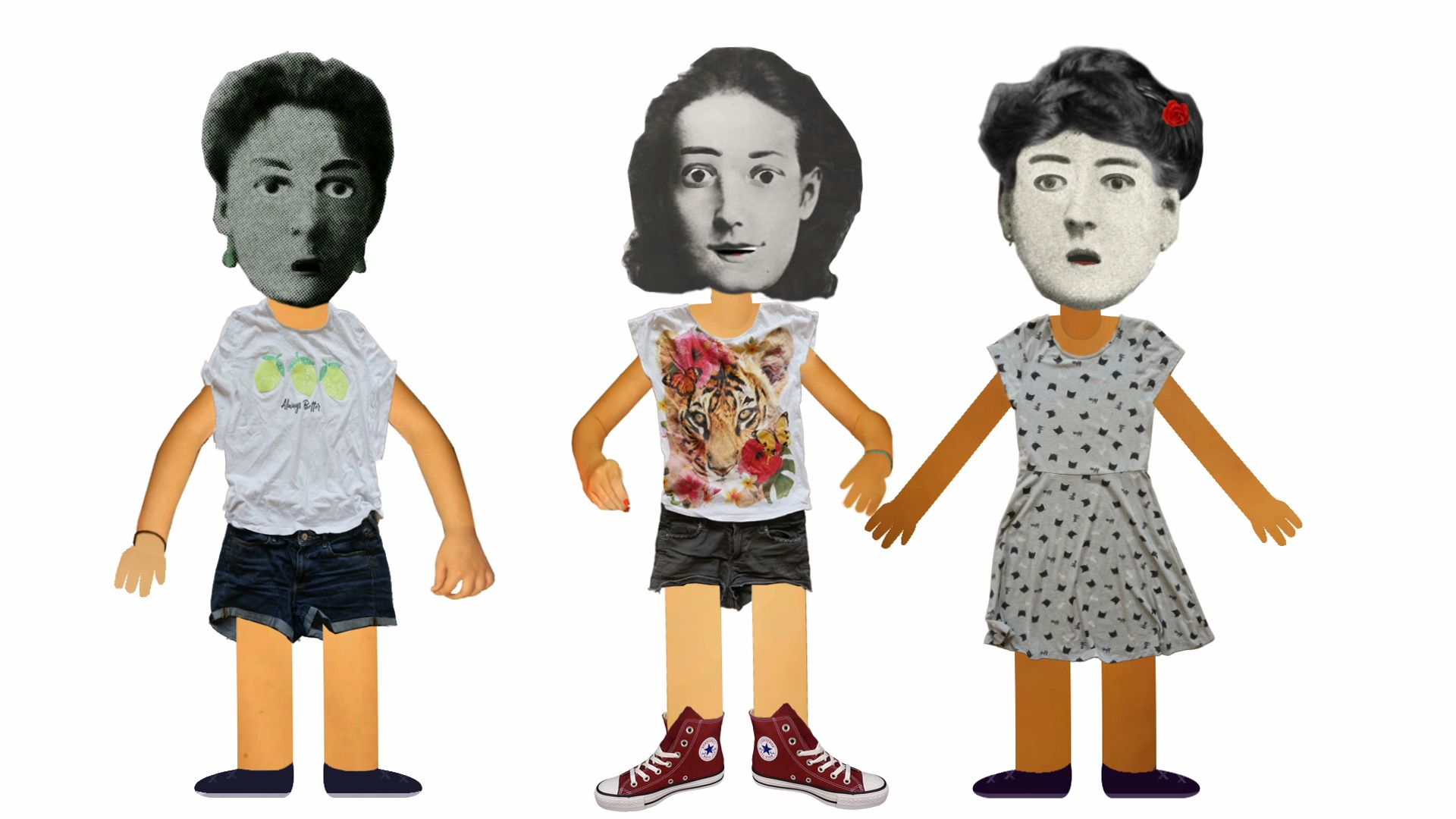

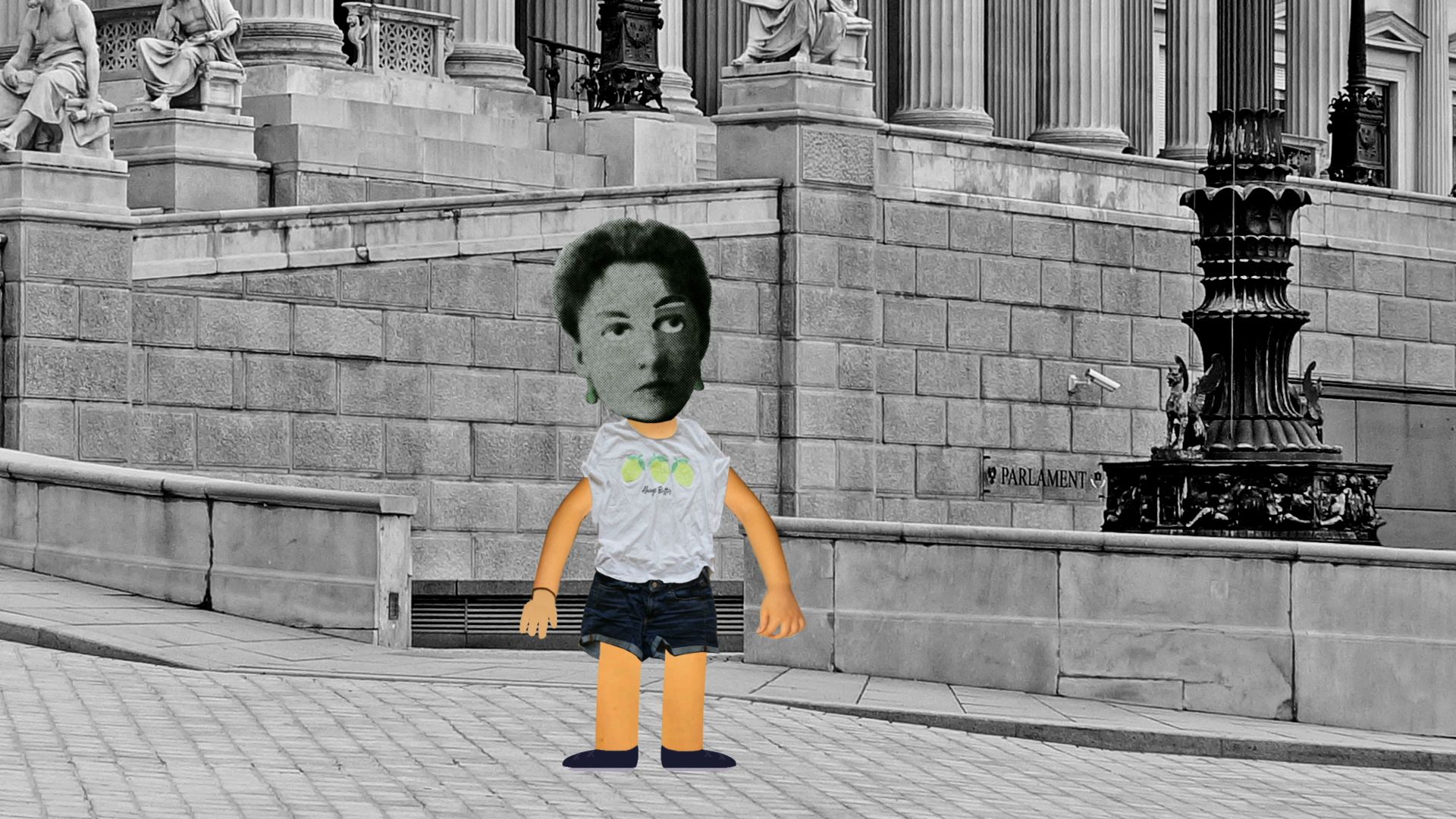

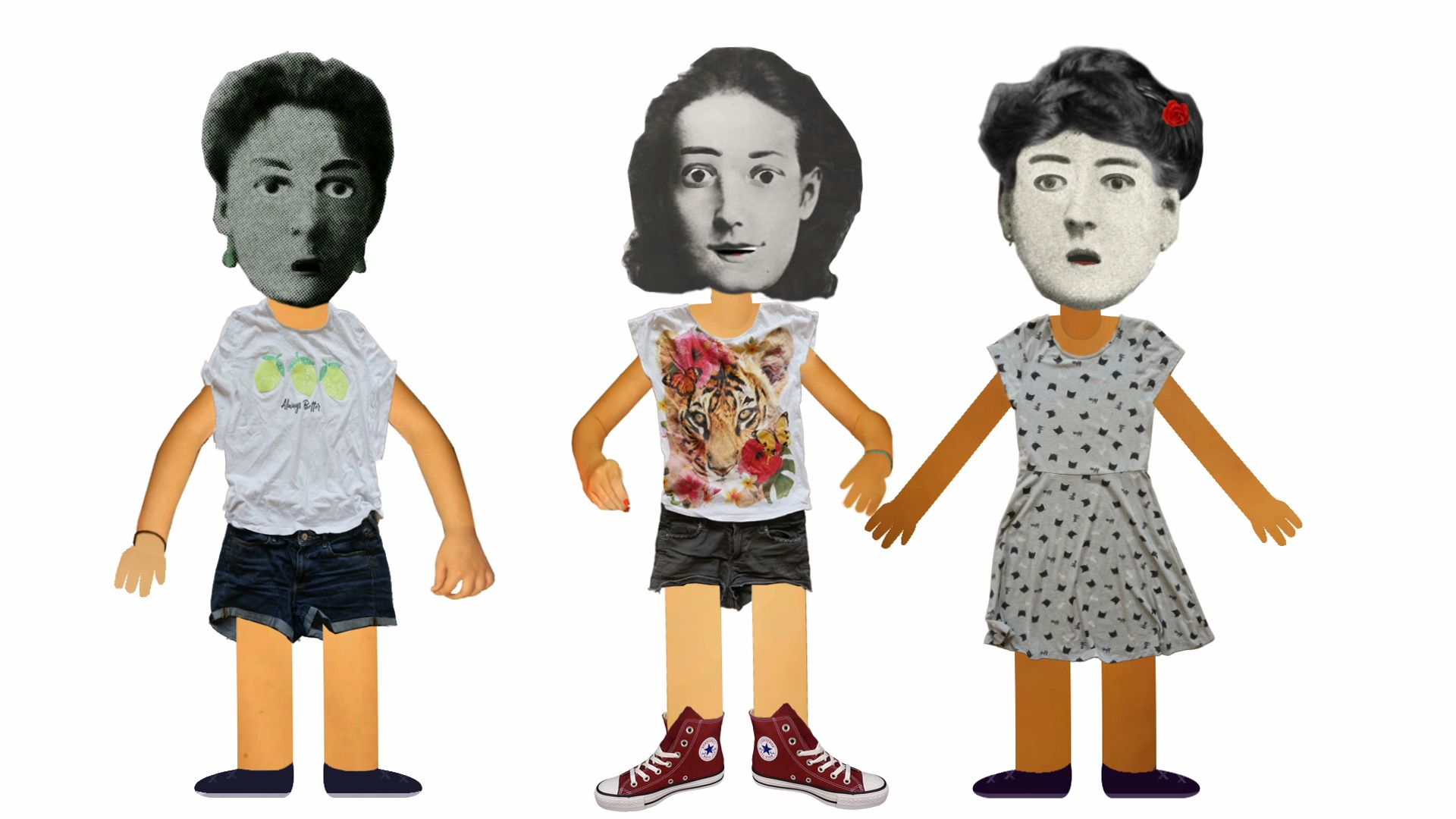

Susi Jirkuff

DIY

Susi Jirkuff has created three animated films that enable students to approach the issue of equality and the history of women’s suffrage in a playful way. With the aesthetics of YouTube videos that are watched and produced by digital natives today in mind, she made three films using cut-out animation in which the figures have the faces of Austrian suffragettes–Anna Boschek, Emmy Freundlich, Marianne Hainisch, and Adelheid Popp–each of whom contributed to the introduction of the women’s right to vote in 1918. These women were also among the first to be elected into the Austrian parliament, along with four others. Their young faces are placed on bodies dressed in the style of young people today to create an aesthetic and thematic link between the seemingly distant past and its relevance for contemporary society. Extensive archive materials and historical pictures and photographs provide the background stories for these figures. Combined with historical facts, these stories form an interesting and educational narrative that especially reaches out to young people.

Three girls lend these courageous women their voices and describe the situation at the time in short biographical anecdotes and quotes. Jirkuff’s narratives create a simple and informative sketch of the social, political, and living conditions of women at the turn of the 20th century, including their lack of access to education, their sometimes strenuous physical labor, which especially poor women were forced to do from the time they were children, and their lack of virtually all rights. Special attention is given to the daily lives of children to give the young viewers a glimpse of how vital the struggle for the right to vote was and the far-reaching consequences this has had for women and children.

The right to vote was a political goal for women of all classes—from uneducated workers to privileged ladies from the upper class. Establishing solidarity and finding a common language was not an easy task, as the short videos demonstrate. As examples, Jirkuff relies on the activists Adelheid Popp (1869–1939) and Anna Boschek (1874–1957) from the social democratic movement, and Marianne Hainisch (1839–1936), who was from a family of industrialists. All of them regarded education for women and girls as fundamental for improving the working conditions and legal situation of women. Hainisch, for instance, helped to establish the first high school for girls in 1892, thereby laying the foundations for the admittance of women to universities and higher education.

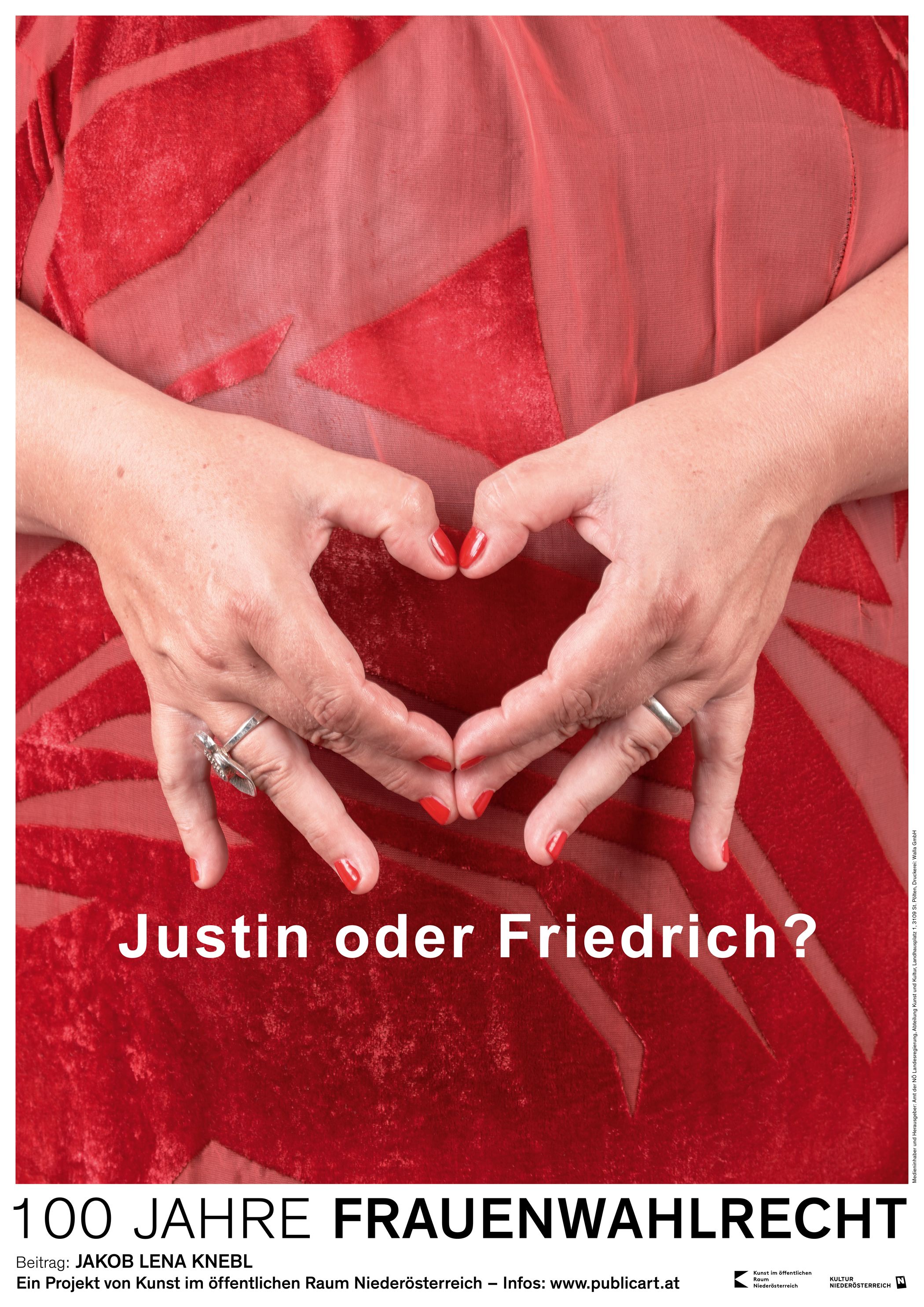

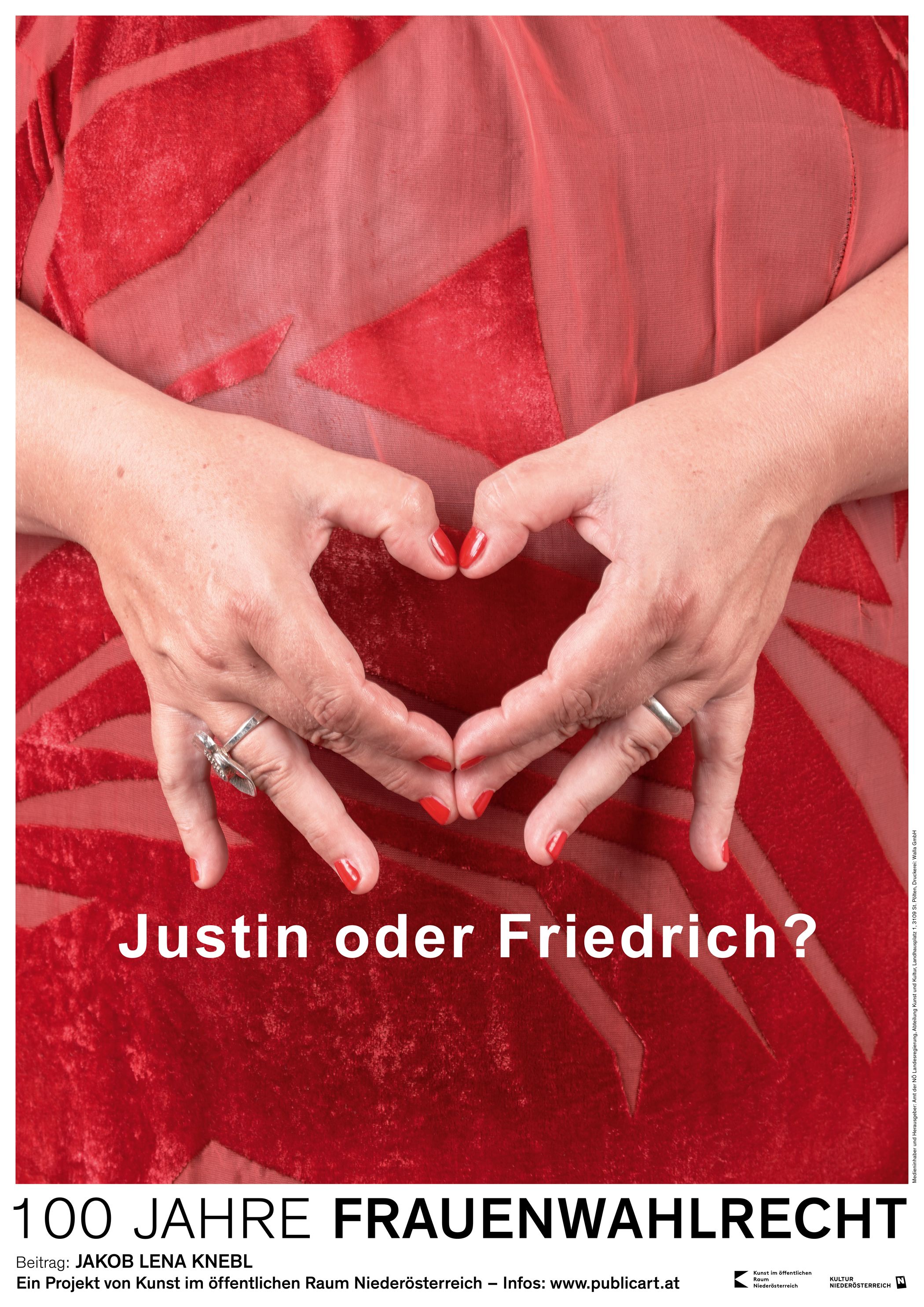

Jakob Lena Knebl

High Heels oder Sneakers

Is choosing the latest fashion accessories more relevant than choosing our political representatives? Is political action and the fight for equality less pressing because of consumerism and the desire to buy the hottest commodities? Although people today seem to agree about feminism, and it appears to have become part of the mainstream, the discussions around it today lack a historical consciousness. The majority of people do not know anything about the long and difficult road the women who fought for the right to vote had to travel.

Jakob Lena Knebl’s series of posters for “100 Years of Women’s Suffrage in Austria” confronts us with such questions. As is often the case with the artist, she approaches the issue with her trademark sense of humor and playful change of perspective. Wearing patterned dresses, she appears decidedly feminine as she tries to make banal everyday choices that seem forced upon her: Which nail polish, which shoes, which partner, which food to eat? The artist deliberately uses product and fashion aesthetics as a medium to convey a socially critical message. She thus relies on a familiar, but bold visual language to grab our attention, thereby making it easy for us to relate to this issue. Her parody underlines the seriousness of other, more important choices that women have today.

The suffragettes, who were especially active in the UK, realized that they would not be able to achieve their goal of political participation if they could not grab and hold the public’s attention. They therefore did not shy away from performative, sometimes very risky, physical involvement. This included marches and acts of civil disobedience, like collectively smoking in public, which was forbidden for women, or mutilating portraits of female nudes in public museums. Through these collectively organized actions and sheer physical involvement, the suffragettes generated the media attention they needed to fuel an ongoing public debate about their demands. This kind of broad impact is something Jakob Lena Knebl also appropriates in her performances and staged photographs, in which she works with her own (usually naked) body.

Her posters also focus on her body in a less obvious way. She presents herself as fragmented, focusing on individual body parts and gestures, while displaying the featured objects like fetishes. The dresses with lively patterns cover her body almost entirely, transforming the fabric into an all-over pattern that serves as a projection surface and backdrop of desire in a parody of the cliché images of women and the mechanisms that have created (and still create) constantly new archetypes. The original opponents of women’s suffrage doubted whether women (in principle) were able to make rational decisions, and in the fog of historical amnesia, some people still think this about women today.

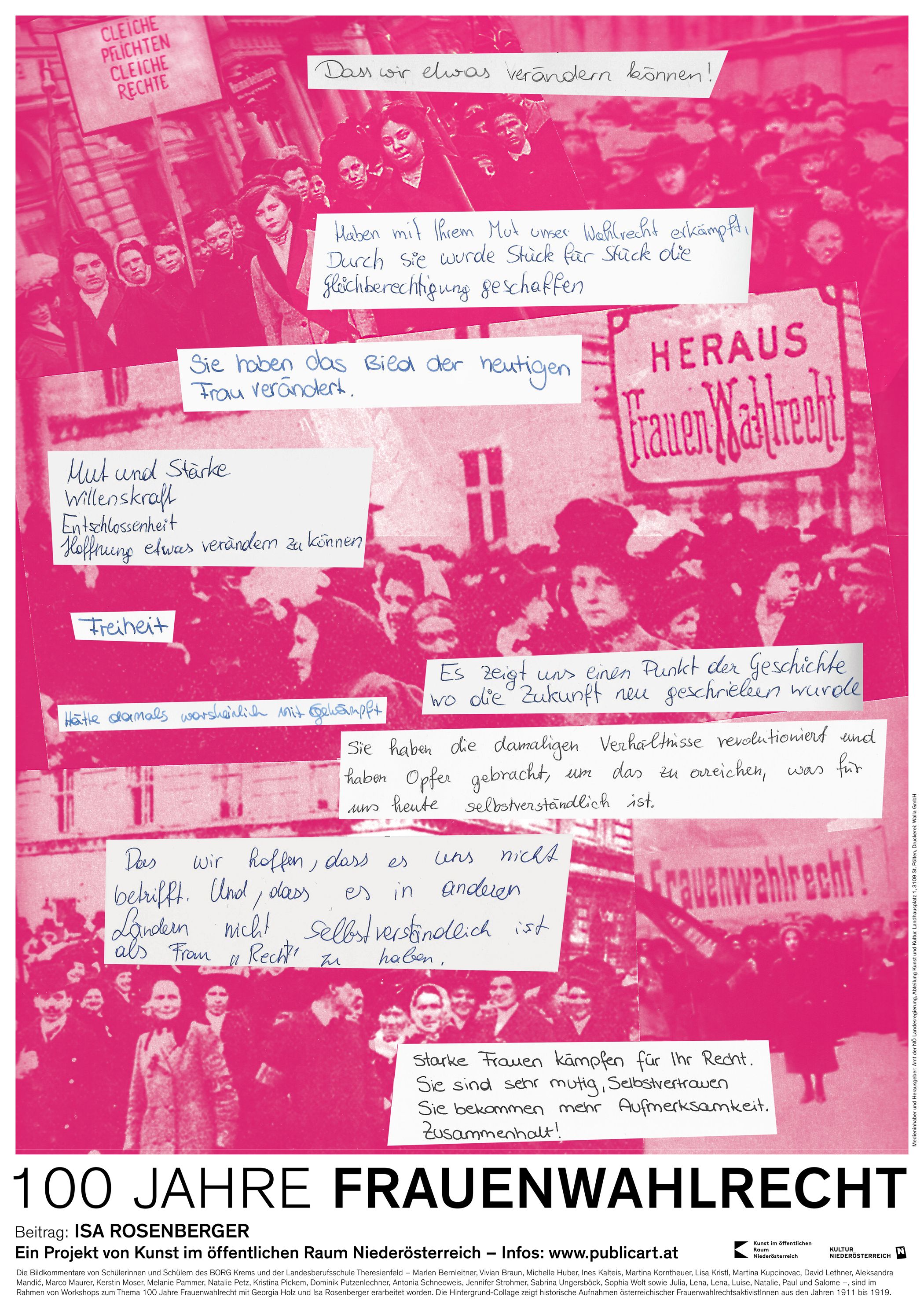

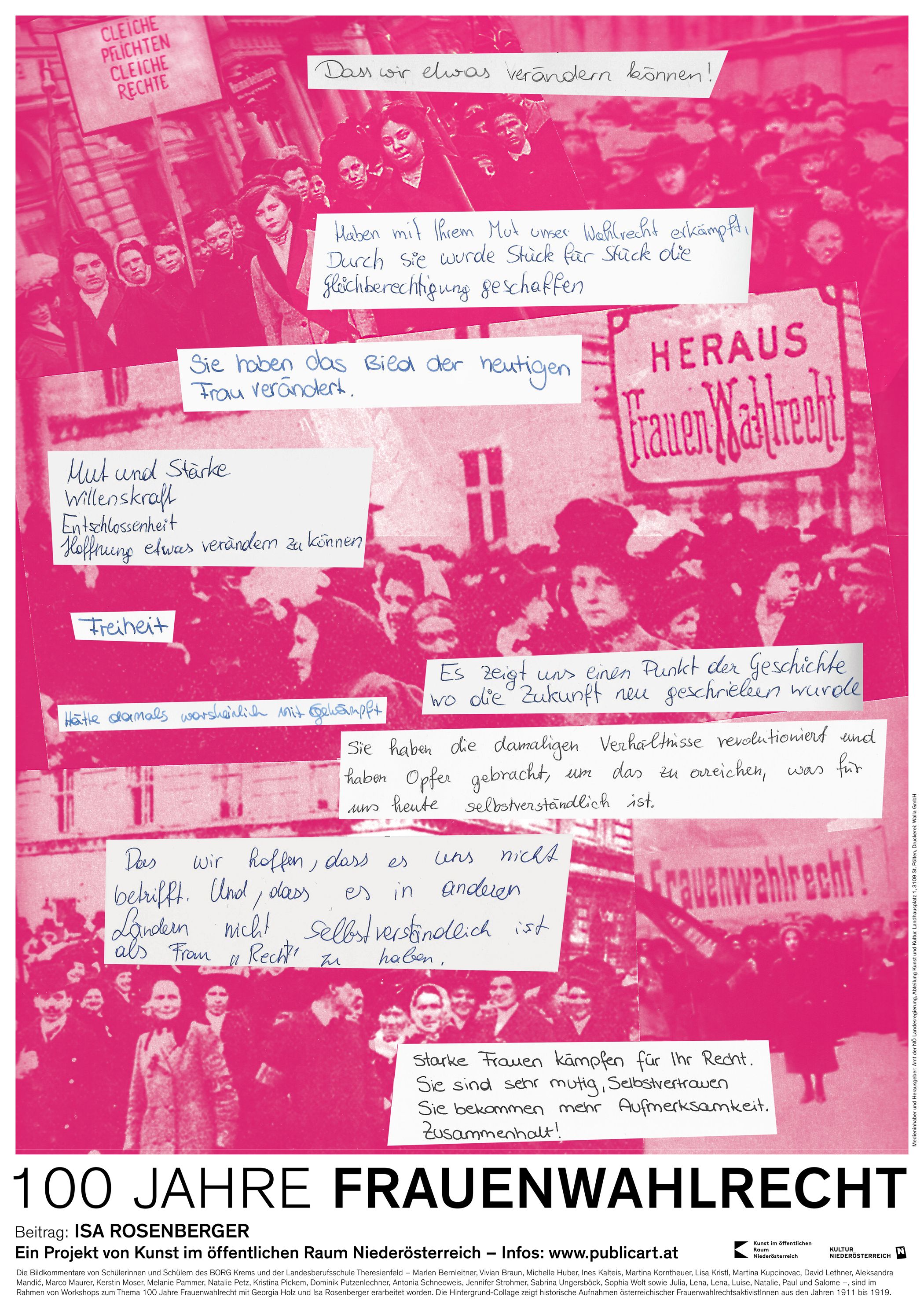

Isa Rosenberger

Isa Rosenberger’s artistic works focus primarily on contextualizing historical events in the present time, recounting history, and questioning established narratives. She frequently concentrates on alternative interpretations or forgotten aspects of history—in this case, concerning the suffragettes in Austria. Through the use of montage, she created a poster design that brings together two levels and two periods by intermingling historical photographs of demonstrating women (and men) with comments by young people today. The selection and composition of the photographs emphasizes physical presence and body politics, while reminding us with what consistency, dedication, and perseverance these valiant women claimed their rights and what repression by the state, hostility, and defamation they frequently had to endure. Although the Austrian women’s movement relied on comparatively less radical means than others, their ingenuity and persistent engagement was in no way inferior to their international comrades-in-arms, for example in the UK. The pictures clearly demonstrate how the wish for political participation brought together women of all classes and ages; the textual level, on the other hand, places their resolve and the unity with which they enforced their demands and acted in public in a new context. “Courage, strength, willpower, and the hope for change” are some of the attributes ascribed to the demonstrators in a comment today—a judgement that would hardly have been shared by their fellow citizens at the time, however.

An essential aspect of Isa Rosenberger’s poster project is her reliance on the participation of school students. She organized several workshops in which she and students discussed the struggle of the suffragettes and the significance of their achievements today, using historical photographs as a basis. Several comments written by the young people in these workshops form the textual level of the poster and interact with the historical photographs to create a kind of dialogue between generations. The pictures reveal “a point in history when the future was rewritten,” as one of the students poignantly states. Today’s generation of young people acknowledges the achievements of these activists and is certainly aware of the relevance of the general right to vote, leaving the question of “What can we do to contribute to a better future?”

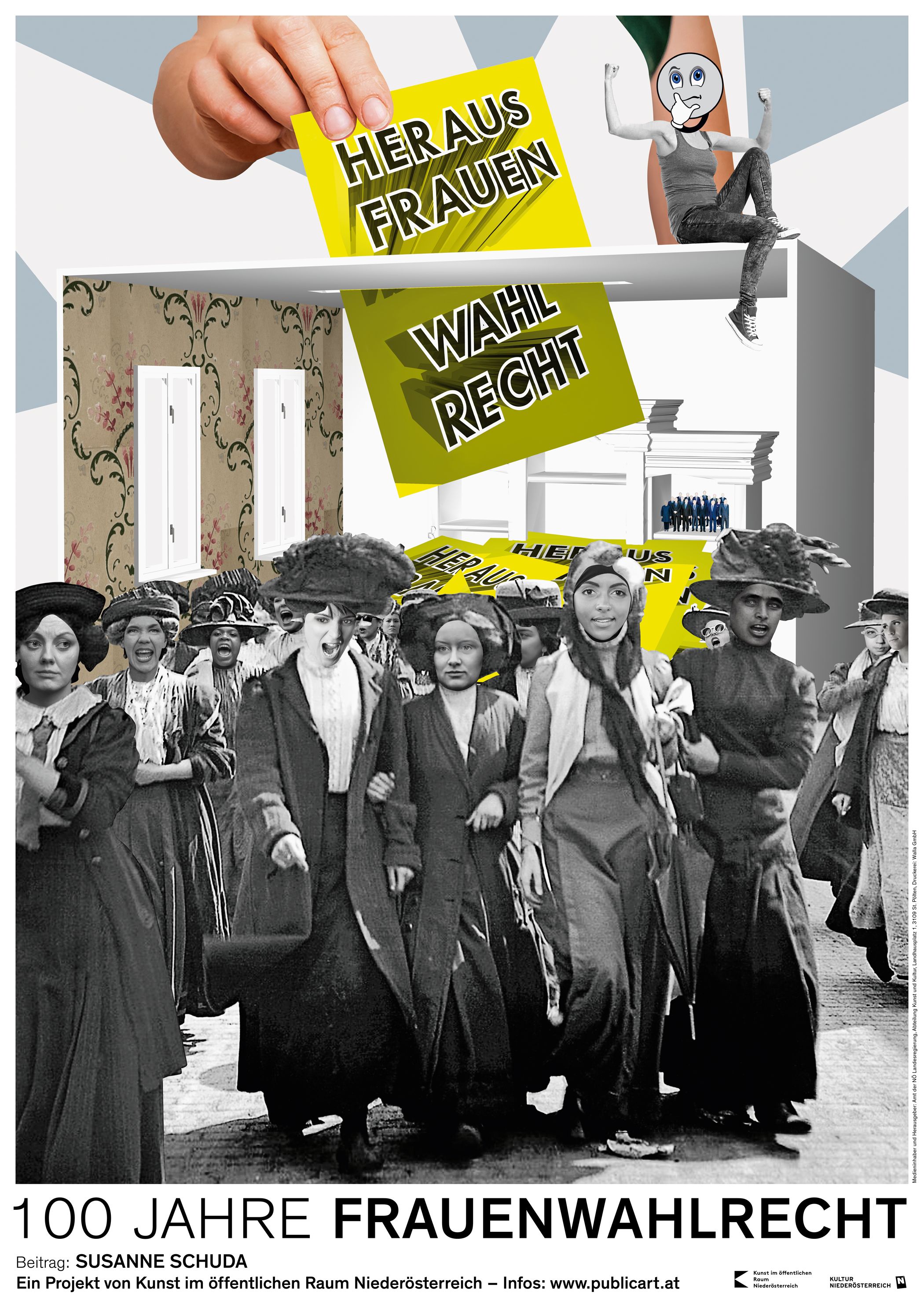

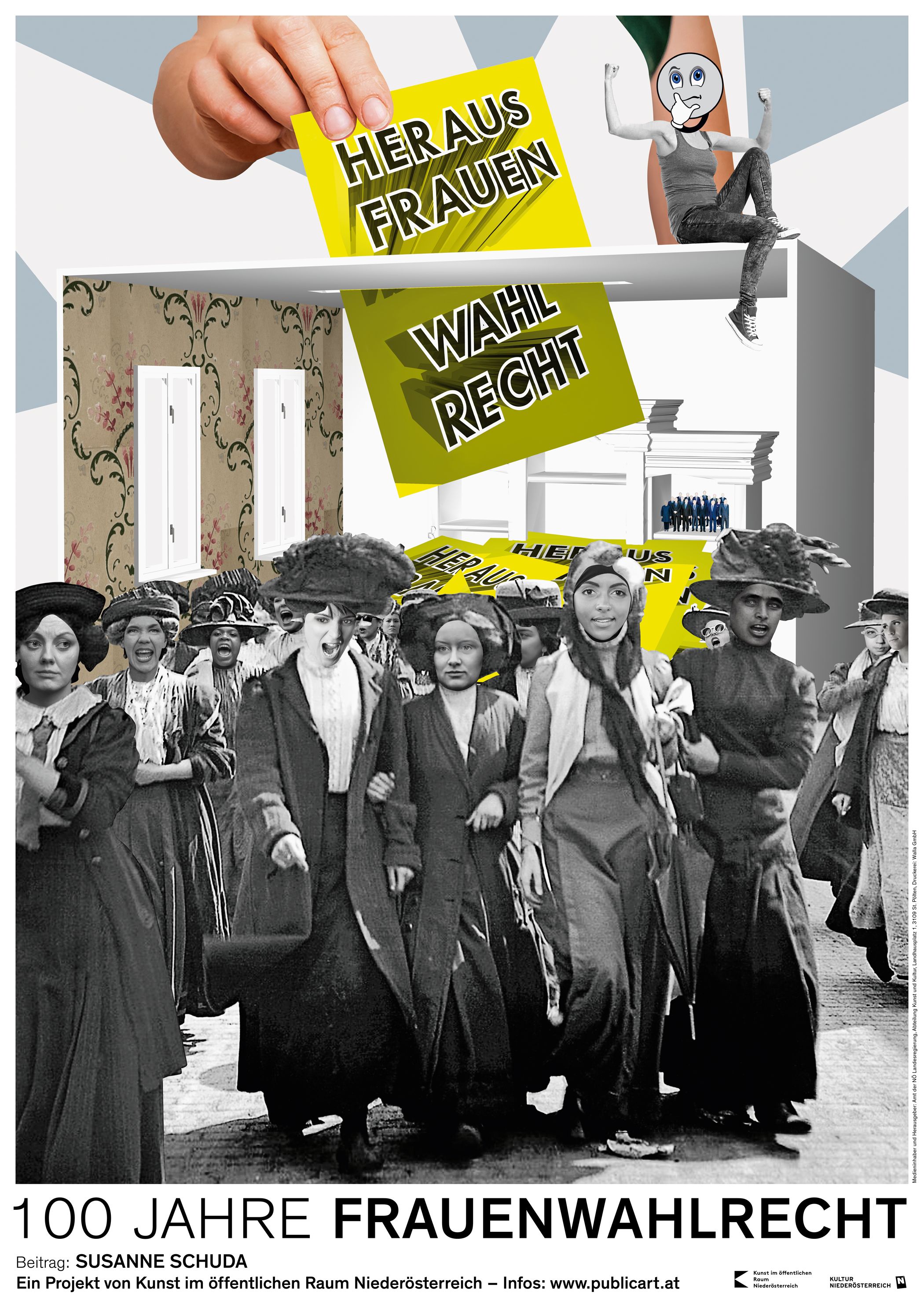

Susanne Schuda

Out Of The Box

Since its invention in the beginning of the 20th century, the collage has become the artistic medium best suited for exaggeration, emphasis, and de- and re-construction. Due to its radical potential and the many different design possibilities it offers, collage is especially befitting for the appropriation and transformation of media images and has traditionally been used for criticizing political systems. The artist Susanne Schuda works with (digital) collage and photo montage as a way of criticizing and focusing on socio-political developments. She is also fascinated by the effects of digital space and related search modalities on collage, exploring how these influence our production of images in general and hers in particular.

Each element in Schuda’s meticulously composed poster design is charged with meaning and conveys a poignant message. “Heraus mit dem Wahlrecht” (‘Let Out’ the Right to Vote) was a combative slogan of those committed women whose goal it was to fight for political participation in Austria at the end of the 19th century. It became a dictum that illustrates the fact that the right to vote was literally kept under lock and key and that the male dominated state was unwilling to allow women to participate in politics. Although Schuda places this slogan at the center of her poster, it is no longer a political demand directed at those who govern, but is printed out on ballots that are cast into a ballot box. This simple shift demonstrates that, although citizens of both genders have the right to vote since 1918, not all of the suffragettes’s demands have been achieved. In Schuda’s poster, this becomes an appeal to all women today not to forfeit the right that was hard won for them, but to use it to change our society for the better. The faces of the demonstrating women in the collage reflect issues such as diversity and solidarity among women, while also pointing to the ambivalences and contradictions that can evolve in any political processes.

Another symbol for this “ambiguity” of the right to vote is the ballot box, the interior of which resembles a domestic scene, traditionally the area identified with women. That the gender gap is still a sad reality (especially in politics) is further illustrated by the small image of a group of anonymous (and for the most part male) “suits,” representing the norm of media coverage. The majority of politicians are still male today, and the promise of freedom, self-determination, and participation for women remains unfulfilled, despite the 100-year anniversary of women’s right to vote. Schuda’s call for women to refuse to be indifferent to the achievements of the suffragettes, to vocally stand up for their own rights and for the rights of others, and to shine a light on injustice is thus all the more pressing. #MeToo and Austrian referendums for equality for women are proof that solidarity and standing together for our beliefs pays off.

Images (15)