Anna Artaker

:

Old Jewish Cemetery in St. Pölten

Back

Information

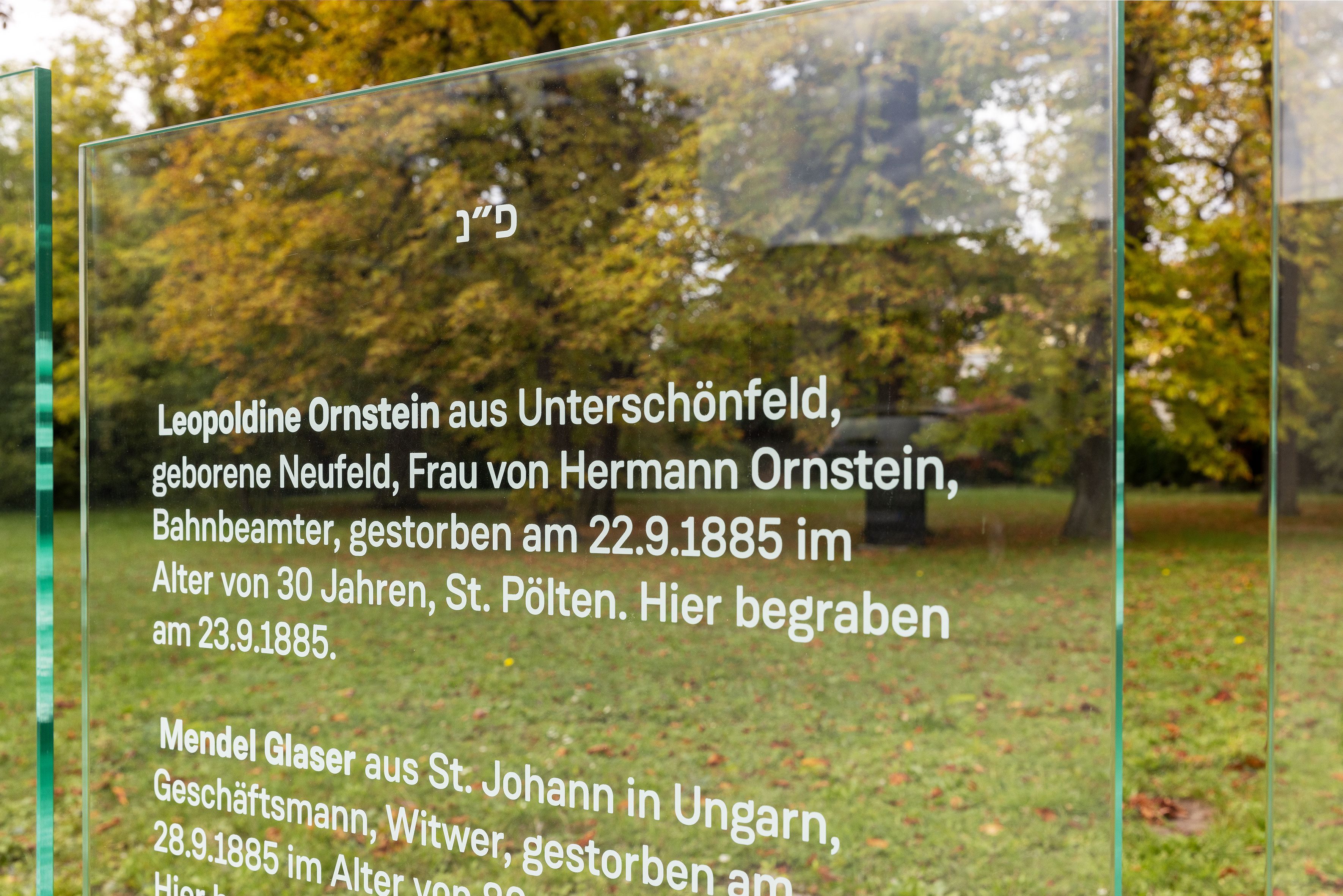

In white writing on transparent glass stands “Daughter of the master tanner Max Frischmann, died November 8, 1875, at the age of a quarter of an hour, Wilhelmsburg. Buried here November 9, 1875.” Behind the writing lies a green meadow. The wind is blowing gently through the old trees. A few chestnuts lie scattered on the ground. The small piece of land in the middle of a residential area is undeveloped and looks like a park. Domesticated nature provides the background for the writing. It is a place of silence, connected to what can be read: “Johanna Steiner, widow of the potash factory owner Benjamin Steiner, died November 29, 1887, at the age of 95, St. Pölten. Buried here December 1, 1887.” While contemplating this, the place behind the words on glass comes back into focus: “Buried here.” “Here” is the old Jewish cemetery in St. Pölten, which the artist Anna Artaker has framed with inscribed glass panels.

Artaker’s artistic, researched-based works explore how reality is the result of a complex intertwining of the world of the senses and the intellect. “How do our words and thoughts influence what we perceive to be reality? And the other way around: How do pictures and objects that we perceive with our senses form the concepts with which we describe our reality?” the artist asks. One central approach is through historiography, which tries to create a picture of the past that is as truthful as possible. This intersection between the past and the present is a focus of Artaker’s works. Her artistic practice often begins in a library, and she frequently relies on historical collections, archive materials, and publications as artistic materials. For her artwork at the old Jewish cemetery in St. Pölten, she also began by consulting primary sources: According to the cemetery’s death records, a total of 544 members of the Jewish Community were buried in this cemetery between 1859 and 1906. After it closed, the Jewish Community buried their dead in the new Jewish cemetery next to the Christian cemetery. In 1938, the old Jewish cemetery was desecrated and the graves were robbed of their tombstones. In 1968, a small memorial stone was erected, which is still standing, in the center of the lot that only indicates the site’s former function. People walking by usually did not recognize the cemetery for what it was, while those interested in its history were unable to find any surviving information, and the bereaved no longer had a personalized place to remember their loved ones.

This disconnect was the starting point for the artist to bring back what had become invisible and make it visible again by lending the cemetery’s history a new, contemporary form. An information panel at the adjacent intersection provides information about the history of the lot in three sections: One map shows where the deceased came from, while another map displays the positions of the graves in the cemetery, which were located without having to dig up the earth. The information also includes a contemporary text about the history of the cemetery. On either side, the information panel is flanked by a row of inscribed glass panes that run along the two edges of the lot that border on public property. The names of the dead are written in white on the transparent glass panes. Similar to what is usually written on a Jewish tombstone, a few lines describe each person. Because the original personalized tombstones were all stolen, the artist decided to use a unified formulation for all the dead. Each inscription begins with the person’s name, their occupation and family relations, and their place of residence. As is the case with many Jewish tombstones, the age of the person at the time of death is listed instead of the date of birth, followed by the burial date. The formulation “buried here” is also one often found on Jewish gravestones (similar to “here lies”). It indicates the person’s last resting place and completes the inscription.

The personal inscriptions that follow this pattern run along the entire cemetery border, creating a rhythm of textual images that enclose the deceased. Each panel begins with an opening Hebrew formulation and closes with a Hebrew blessing. For those who cannot read Hebrew, the panels thus create an ornamental and sign-like impression, while providing those who can the chance to observe the rituals of remembering the dead. Panel for panel, page for page, line for line: The white letters on the glass re-create the open pages of the death records, each panel in portrait format could be read as a transparent page of a book. Artaker chose the color white for the writing in reference to the traditionally white garments for the dead in Judaism. The white writing is also very visible against the background of the green meadow and hence inscribes itself continuously into the place. “The view of the cemetery is thus connected with the names of the people to whom according to the Jewish religious teachings this walled-in lot belongs—namely, those who have found their final resting place here,” writes the artist. Because looking through the glass panes at the cemetery behind them also defines the cemetery as a readable place, Artaker’s work demonstrates the great importance of the written word in Judaism, which is a religion of holy scriptures.

Artaker explored the Jewish community’s affinity for writing already in her installation WIENER AUTOGRAMME 1305–1380 (VIENNESE AUTOGRAPHS 1305–1380) (2020–21), which can be seen in the permanent exhibition of the Jewish Museum at Judenplatz in Vienna. Reading the Torah in the temple is an important part of practicing this religion, and as a consequence, the Jewish community became highly literate early on. Already in the Middle Ages, many Jewish people could read and write. Unlike the Christian majority, who certified documents with a seal, Jews were already accustomed to certifying contracts with their hand-written signature. That is why, out of the members of the medieval Jewish community in Vienna, 18 names are preserved in their own handwriting. The artist used this particular aspect as a starting point for the WIENER AUTOGRAMME 1305–1380 in which white light traces the names in the original handwriting before a typographical transcription into Hebrew and finally a typographical German translation is added. Following this scheme, the projection of letters runs its course and not only represents the Jewish population of medieval Vienna through the written word; it also makes it legible through its transcription and translation into the two languages of Hebrew and German, thus rendering it accessible to museum visitors today. The artist explains that “the projection of the signatures and transcriptions is a metaphor for the fleetingness of our access to this past, which can come to life for us only rudimentarily and for a brief moment.” While the names in the projection in the Jewish Museum alternate, the names in St. Pölten are permanently inscribed. The fleetingness of the projected signatures in the work made for the museum contrasts with the permanence of the commemoration of the dead in her project for the cemetery. At the same time, both works make names that had become more or less illegible readable again, lending them presence.

Names are also formative for the installation OUTSIDE | INSIDE, which Artaker realized for the European Forum Alpbach in 2020–21. On the glass exterior of the Congress Centrum in Alpbach, the artist listed the names of all the speakers over the 75-year history of the forum. The names of the men and women were given different typographic treatment: those of the women, like the years, are printed bold and can be read from the outside, while the names of the men can only be read from the inside of the building. “This arrangement clearly demonstrates that women were only invited to Alpbach as speakers in exceptional cases up until the 2000s: among the almost 16,500 names, only a little more than 3,300 are women […], despite the fact that women have played a major role not only in the important network character of the European Forum Alpbach,” the artists notes. Through the gender-specific organization of the names on the glass walls, part of the writing appears mirror- inverted and hence both flush-right and flush-left. The reading directions also cross in the Jewish Museum in Vienna and in the old Jewish cemetery in St. Pölten, because Hebrew is read from right to left. Through such writing inversions, the reading eye pauses, signs become visible, and readers begin to reflect on their own perspective. In the case of OUTSIDE | INSIDE, the position of the readers is decisive for whether the names can be read or seen. Visitors are made aware of their personal perspective in a similar way at the old Jewish cemetery in St. Pölten: While the names can be read back and forth from the streetside, they are transformed into mirror-inverted symbols when seen from the inside of the cemetery. Through the transparent glass panels, the personalized remembrance of the dead remains connected with the public realm—with the writing working as a pictorial and an informative medium.

Artaker’s glass panes with their white writing enclose the old Jewish cemetery today and accentuate the view of those passing by, of those who stop, and of those who remember. The old Jewish cemetery in St. Pölten thus becomes a visible place, andour eyes are opened to it by seeing through reading: The writing is localized by what is behind it. It becomes a historical surface and creates a site of remembrance. From the opposite perspective, the surroundings become an emblematic frame that conscientiously gives memory a home. Artaker’s installation of inscribed glass panels situates the old Jewish cemetery between visibility and readability as a site for a quiet remembrance, the history of which is closely connected with writing and is thus tied to a historical understanding of our present time.

Hannah Bruckmüller

Images (8)