Anne Schneider

:

Geburt der Venus

Back

Information

Anne Schneider’s newborn Venus does not correspond to an ideal or strive to fulfill expectations regarding appearance. She stands before us newborn, without any responsibilities or attributes. She hasn’t yet taken her final shape, nor has she been formed by her environment. Quite the opposite – reacting to the space around her, she is in the state of turning inside out, for what is birth if not the insistence of a body to reach the outside?

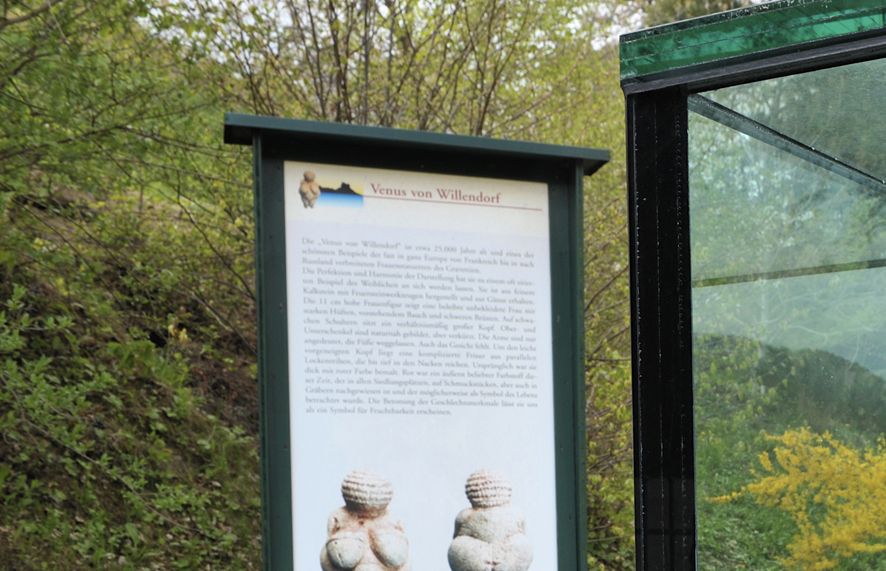

Beginning with one of the oldest known sculptural forms from the Stone Age, the Venus of Willendorf, and leading up to the Aphrodite of Knidos by the ancient Greek sculptor Praxiteles, up to Sandro Botticelli’s painted Venus born out of sea foam in the fifteenth century, the idea of Venus has always been associated with a certain degree of idealizing: Neither the excessive corpulence of prehistoric times, nor the straight bodies of antiquity, or the proportions of the golden ratio of the Renaissance were based on reality. Anne Schneider’s newborn Venus does not correspond to an ideal or strive to fulfill expectations regarding appearance. She stands before us newborn, without any responsibilities or attributes. She hasn’t yet taken her final shape, nor has she been formed by her environment. Quite the opposite – reacting to the space around her, she is in the state of turning inside out, for what is birth if not the insistence of a body to reach the outside? This work is a kind of "primal bündle" made of colored concrete that seems to want untangling and lacks the characteristics of – but not the potential to become – a woman’s body. We see a Venus not yet shaped by society or the environment: a female body without a defined social role. It is an ideal that has no equivalent in reality. Like her prehistoric predecessor, Anne Schneider’s concrete-cast Venus is strongly corporeal. Although we are surrounded by it in our everyday lives and quite literally live in it, concrete is a material that is normally processed without leaving any attributable human traces. In contrast, Anne Schneider’s working method lends human traces, folds, bulges, and scars to the material, giving it an organic character and conveying the human contradiction often found between form and content, or between appearance and essence. Instead of a soft interior beneath a rough exterior, we encounter a rock-hard material that appears to have a soft surface.

The seams of the textile mold from which Venus was born are the only traces of where she came from on her way to gaining new experiences in her new home – a place where she can be viewed from all sides. Exposed to the gaze of visitors without any protection, but well-protected by the specially engineered glass structure, she brings life to the glass case in Willendorf, turning it into an incubator for the months she inhabits it (after leaving her organic interior space). Her future development is located between transparency and stability, possibly marking the beginning of a long line of descendants.