Where Do the Borders Go?

BackArtists

- With

Information

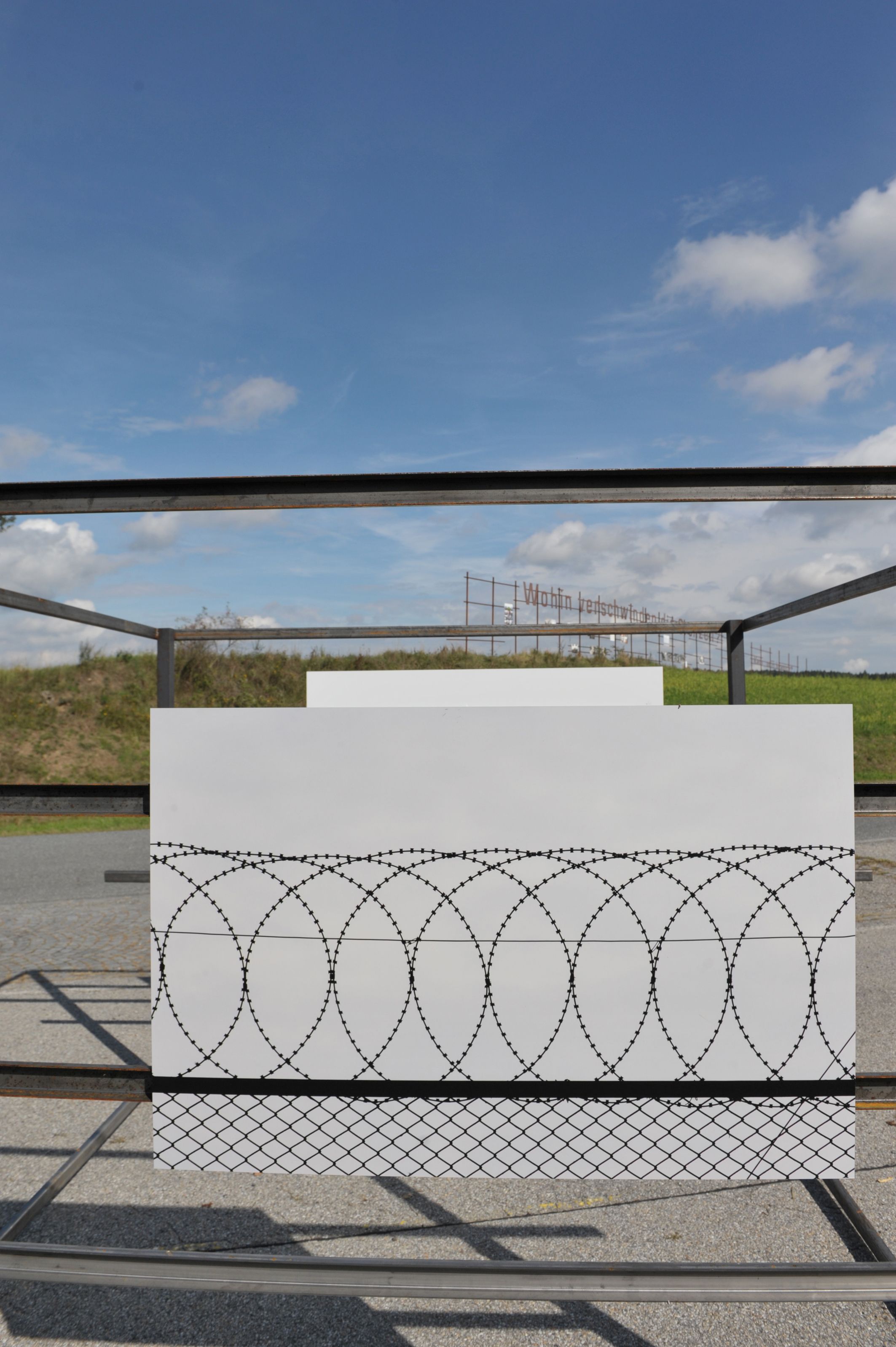

The visible borders in the European Union are being dismantled one by one and are disappearing according to a schedule. At least, that is how it seems. The question of Where Do the Borders Go? is thus rather paradoxical. If they were truly vanishing, we would not have to ask where they were going. Yet they are moving to the external borders of the EU, only to reappear in a very similar form as before: with barbed-wire fences, barriers, walls, the rigorous surveillance of people and goods, and so forth. They are also moving from the perimeter to the inside of the country in the form of discussions about guarded and gated residential areas, security measures, migration, right of residence, and so forth. The work Where Do the Borders Go? is located in the town of Fratres, next to a border checkpoint between Austria and the Czech Republic that was built in the early 1990s. The metal construction is 4 meters high and more than 50 meters long. It serves as a display board for messages and picture panels, and it also points out the public and private strategies to maintain social separation.

Amateur actors with immigrant backgrounds living in the Czech city of Čížov, where one of the last pieces of the Iron Curtain still stands as a kind of memorial, collaborated to produce an artwork that formed the centerpiece of the structure for two years. The work consisted of photographs that slowly became bleached by the wind and weather and were finally taken down in the fall of 2012. After this, it was decided to continue this project, which had been started in 2009, because the debates had since evolved and become more urgent. The border structures between the Schengen countries have actually been dismantled for the most part, and everything resembling a border in the traditional sense has been taken down and sold off. The border stations have been privatized; the annexes, fortifications, gates, control booths and so forth have been removed. Gone with them is a piece of recent history, leaving us its witnesses. While we have more freedom in the EU today, we are also more anxious about the stream of refugees pouring in from war zones and crisis areas and the realization that fences and walls are now being built somewhere else. Fortress Europe is trying to barricade itself from intruders along external borders. It is charging international security firms with the surveillance and protection of its borders, the apprehension and deportation of people crossing over by foot, boat, or (motorized) vehicle, and the maintenance of the status quo for Europeans. Several states are building unpassable walls, while others are considering following in their footsteps. State-of-the-art barbed-wire and security barriers measuring several meters in height protect the outer European border in Morocco, where the "border problem" has been outsourced to a non-EU country. Every day, we read about the rising number of people who have died or been apprehended at invisible yet effective borders – people who failed to achieve their dream of a better life. The question “Where Do the Borders Go? / Kam mizí hranice?” is more urgent in 2014 than ever before. While it is only right that we celebrate the fall of the Iron Curtain, this project is an attempt to direct our attention toward new borders and walls and to raise our awareness of the importance of a continuous peace effort. To this end, we invited artists from the Czech Republic, Poland, and Austria to address and reflect on former, current, and future discourses on borders.

(Iris Andraschek and Hubert Lobnig)

Contributors

- Kuration

Contributions

Katrin Hornek

„UPSTREAM“ The Colorado River has played a major role in the mythical conquest of the American West. To this day, agriculture, drinking water, and electricity in the desert region of the Southwest of the US depend heavily on the water management of the Colorado River. The political future of the river was decided in 1922 with the “Law of the River.” The law divided the water between the bordering states and Mexico and thus decided what areas would be developed economically and what areas would remain desert. The main control center of the river is the Hoover Dam. Upstream from the dam, the Grand Canyon serves as a kind of natural monument for the river. Downstream of the dam, at the southern end, most of the remaining Colorado River is redirected via the All-American Canal, which also marks the border between Mexico and the US, to Imperial Valley—a gigantic, irrigated framing area in California. Through the overuse of the Colorado since the 1960s, hardly any water reaches the sea anymore, because it is redirected to the large agro-industrial fields before reaching the Mexican border.

Agnieszka Kalinowska

Agnieszka Kalinowska developed a new work called „WELCOME” for this project. The letters spelling this word were cut out of aged and heavily corroded metal and then mounted on the display structure. The word looks decrepit and has holes that could be from bullets, while some letters are barely legible due to severe destruction. Over the years it has been mounted, the lettering has corroded even more through wind and weather. The artist said, “Greeting someone ‘at the door’ in today’s terms is, rather, a diplomatic effort. It is more a case of the host screening the flow of guests. Those who are happily peaceful and well-off don't welcome refugees seeking shelter with open arms. Instead, they put up signs saying ‘Welcome’ at the border.

Lukáš Houdek

The work „The Art of Killing“ consist of a series of twenty-five black-and-white photographs in which massacres of German civilians in 1945 in the Czech Republic are reenacted with puppets in exemplary scenes The artist said, “Especially after the end of the war and before the Potsdam Agreement that laid down the conditions regarding the expatriation of the Germans from the Czech borderland, thousands of German civilians were killed as a result of collective guilt, along with people who participated in the anti-Nazi resistance, foreigners, and Jews. The instigators of these brutal acts were often members of Revolutionary Guards (sometimes nicknamed the Looting Guards), units recruited from partisans and volunteers after the Prague Uprising. Similar conduct was adopted by some of the members of the Red Army and the reconstituted Czechoslovak Army.

„The Art of Settling“ is a follow-up to the project entitled The Art of Killing (2012). It draws on archival materials from a dossier named “Settling Committee” kept at the State District Archive in the town of Tachov. These materials provide an authentic documentation of the nature of the recruitment campaign targeted at future settlers. They also document the subsequent living conditions of the families who settled in this bleak border region.

Franz Kapfer

„Arabesken“. Franz Kapfer chose to show a series of outdoor photographs of the upper edges of walls, taken in Istanbul in 2014. Lines and dots intertwine in circles against the strong light of the sky in the background, reminding us of arabesques and ornaments. Razor barbed wire—in German also called “NATO wire”— is mounted in special formations to achieve maximum effectiveness as a fortification. Razor barbed wire consists of a thin metal strip with embossed sharp blades and has been in use since the 1960s. It has now replaced regular barbed wire, which has twisted wires with sharp points, in certain areas and is usually employed for military purposes or to secure border fences.

Abbé J. Libansky

“Grenzen im Kopf”. When the so-called Beneš decrees became important in the context of negotiations about the Czech Republic joining the EU in 2001, Abbé J. Libansky placed 250 busts of the former Czech president Edvard Beneš directly along the Austrian-Czech border between Fratres and Slavonice. He also invited representatives from all political parties from both countries to sit down at the border and talk to each other directly about this still open, sad chapter of their shared history. No one came. Since then, the border fence has disappeared, but the border is still intact in our minds due to issues like these. The Beneš heads may be collecting dust, but they are still there today.

Zbigniew Libera

In his works, Libera often plays with (visual) associations and memory. “History Lesson”, which is a part of a multi-partite work called New Histories, puts fears, ambiguities, and nightmares in an undefined time and space. We can see three horses with riders in front of an empty, half-destroyed apartment building. The picture has an extreme landscape format. Are the riders anarchists, punks, outlaws, or soldiers in a private army? The picture looks like an urban dystopia, a world devastated from catastrophe or war—a world where nothing is how it should be.

In order to understand this photograph, it is important to know that it was taken in Borne Sulinowo (Groß Born in German), a town of 4,500 inhabitants in Poland. After a military base was built near the train station there, it was significantly expanded in the 1930s, after which it acquired the name Westfalenhof in the Third Reich. In 1943, it became a garrison of the German Armed Forces, and between 1939 and the end of the war, there was a POW camp there. After 1945, Borne Sulinowo became a garrison of the Red Army and fell under its administration. Up until 1993, fifteen thousand soldiers were living there. After the withdrawal of Soviet forces in 1993, the base was looted and destroyed and now stands empty.

Heidi Schatzl

“THEY MAY HAVE STOLE OUR BANNER BUT THEY WILL NEVER STEAL OUR CULTURE”. The structure of the city of Belfast, Northern Ireland, reflects opposing political positions. Outside the city center, wall paintings covering entire houses express the opinions of the politically divided population. In Belfast, a house is only meant for living on the inside; its outside sends a political message in an expansive mural that covers entire walls. Visible from far away, the wall paintings mark territories. The murals differ in character: some are threats, some are corrections, memorials, reminders, or existential statements.They carry the potential for reconciliation because they make it possible to state contradictory messages in urban space in the long term and thus initiate a broader discussion.

“How to Draw a Line?” In photographs of Jerusalem and Hebron, a kind of urbanism based on opposing political views becomes visible. The border between Israel and the Palestinian territories runs through the streets of these two cities, parts of which are much older than the Oslo Peace Agreement from 1994, which drew the borders for a planned two-state solution for the first time. The grave of Abraham in the Cave of Machpelah in Hebron, which is a key site for both religions, is now half synagogue, half mosque, with the same wall frieze running through both states. A building can also be located in an Arab zone, while its roof is occupied by Israel and transformed into a viewpoint with containers and plastic chairs. Thus, the temporary borders between the two states can run through buildings. Palestinian markets, for example, are often covered with roofs made of metal sheets, lending them a mobile character. In these two cities, it seems as if borders are often fiercely contested, while they also remain recent, changeable, and impermanent.

Johanna Tinzl, Stefan Flunger

The photographic series „Framing the Fringe“ evolved during a drive along the eastern borders of the European Union. At the center of each photograph is a conventional navigational device, showing that the picture was taken exactly at the outer border, with the landscape surrounding the border in the background. The perimeter of each picture frame corresponds to the length of the EU’s outer border in the country it was taken—in other words, the length of the border between Estonia and Russia, Lithuania and Kaliningrad, Poland and Kaliningrad, Lithuania and Belarus, Latvia and Russia, Latvia and Belarus, Poland and Belarus, Poland and Ukraine, Rumania and Ukraine, Rumania and Moldavia, Hungary and Ukraine, Slovakia and Ukraine, Bulgaria and Turkey, Greece and Turkey, and the de facto border dividing Cyprus.

Images (7)