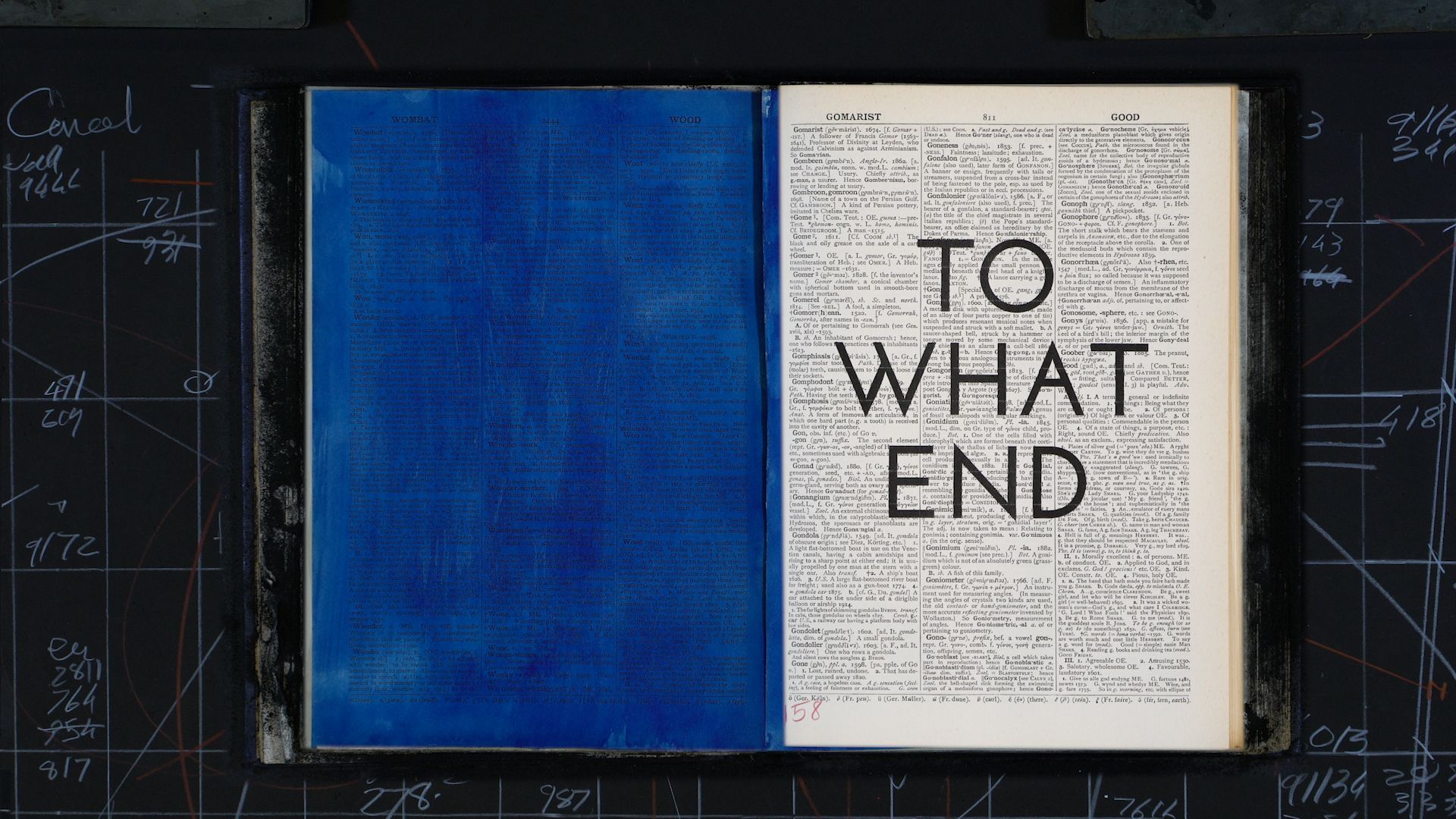

What can be done? – Practices of Solidarity

BackArtists

- With

Information

What can be done? is an outdoor exhibition of contemporary art spread throughout the town of Traiskirchen that addresses issues of social participation and solidarity with a focus on current and historical contexts.

Traiskirchen has many facets. It also has a rich history as an important industrial center from the 18th century on and managed to reinvent itself after the end of the industrial boom. The former factory halls, where goods for the entire world were manufactured for many years, have housed new trades and service providers for a while now. The Wiener Neustadt Canal, which was once an important route for transporting goods, is now a recreational area, and winegrowing is still an important part of the cultural heritage of the city and the entire region. The spirit of the former working-class town is still omnipresent with regard to politics as well.

However, Traiskirchen is also a town that left its mark on the collective memory of Austrians in 2015, if not before. The reception center for refugees (German: Erstaufnahmestelle Ost) has reflected the geopolitical conflicts within and beyond Europe since the 1950s. In 1956, refugees primarily from Hungary arrived at the reception center in Traiskirchen, which was initially established as a temporary solution. Later, people from Czechoslovakia, Chile, Poland, and Romania came; then in the 1990s, people fled the Balkan Wars, and from the end of the 1990s on, refugees came from Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. In 2015, 4,500 people were living in the reception center, setting a new record.

At the same time, Traiskirchen has also become a symbol of acts of solidarity, thanks to its strong civil society. It is a very ambivalent place.

In light of the current war in Europe, people express their solidarity and call for a united Europe, one that stands together. Although the word “solidarity” is used almost excessively, it does not seem to apply to everyone.

What does solidarity mean within and beyond Europe today? Old conflicts apparently continue to persist, and new crisis areas are constantly emerging. Instead of true cooperation, national isolationist tendencies are creating rifts in the European Union, trying its resilience. The COVID-19 pandemic has impressively shown how people in society as a whole first closed ranks and then began to increasingly follow their individual interests.

While the current war continues to leave many people shocked, and immigration policy makers struggle to find the right solutions, civil society is increasingly providing urgently needed help. Many people ask themselves, “What can we do?”

Do European policies have the potential to create a society based on solidarity that is ready for the future? Negotiating ideas about how people can live together is done not only on the level of politics, but also in classrooms, at universities, on the streets, and most importantly in people’s private lives. This conversation can be felt clearly in Traiskirchen.

What can contemporary art achieve in this tension-riddled context? At a time when we are facing great challenges, art is capable of working through things, visualizing ideas, keeping discourses open, and perhaps contributing to making alternative social approaches palpable and hence imaginable through action and initiatives based on solidarity and communal dynamics.

The site-specific works in this exhibition explore issues like migration, personal freedom, acts of solidarity and moral courage, current societal challenges, as well as personal dreams and wishes.

Contributors

- Kuration

Contributions

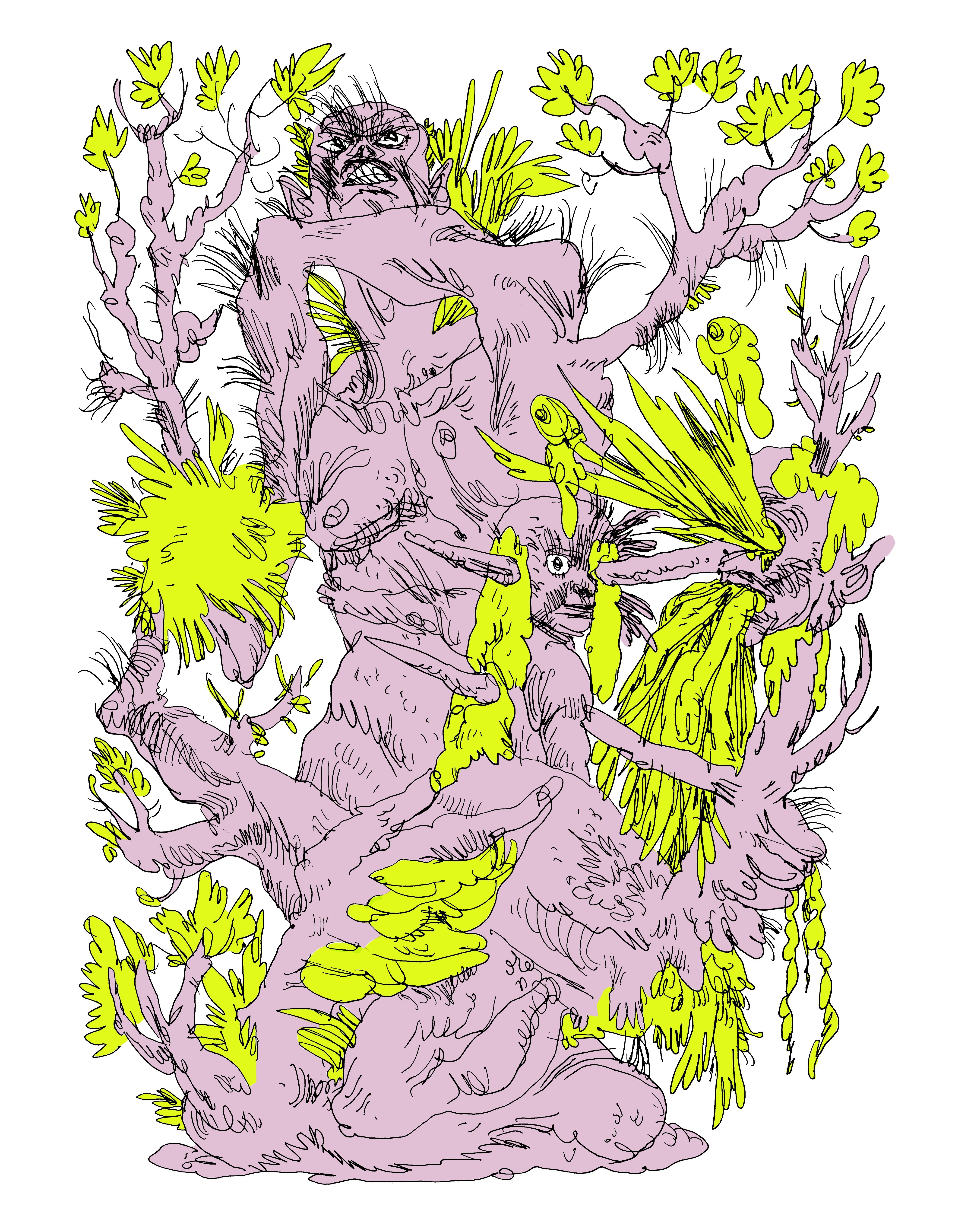

Anatoly Belov

Mysterious Forest

Trees and plants travel. Although they are rooted in the earth beneath them, they migrate, albeit slower than humans and animals. They migrate over generations. External circumstances cause them to adapt. They migrate to survive.

Anatoly Belov’s series Mysterious Forest explores the question of survival and adapting to external circumstances. His trees change: They merge into dream-like hybrids of human, animal, and plant. They are part of the universe of Cybele, the Roman mother of the gods. Her myth revolves around the dualism of the sexes, because she evolved when the masculine half was liberated from a demonic hermaphrodite. Gender identities, queerness, and sexuality are recurring themes in Anatoly Belov’s artworks.

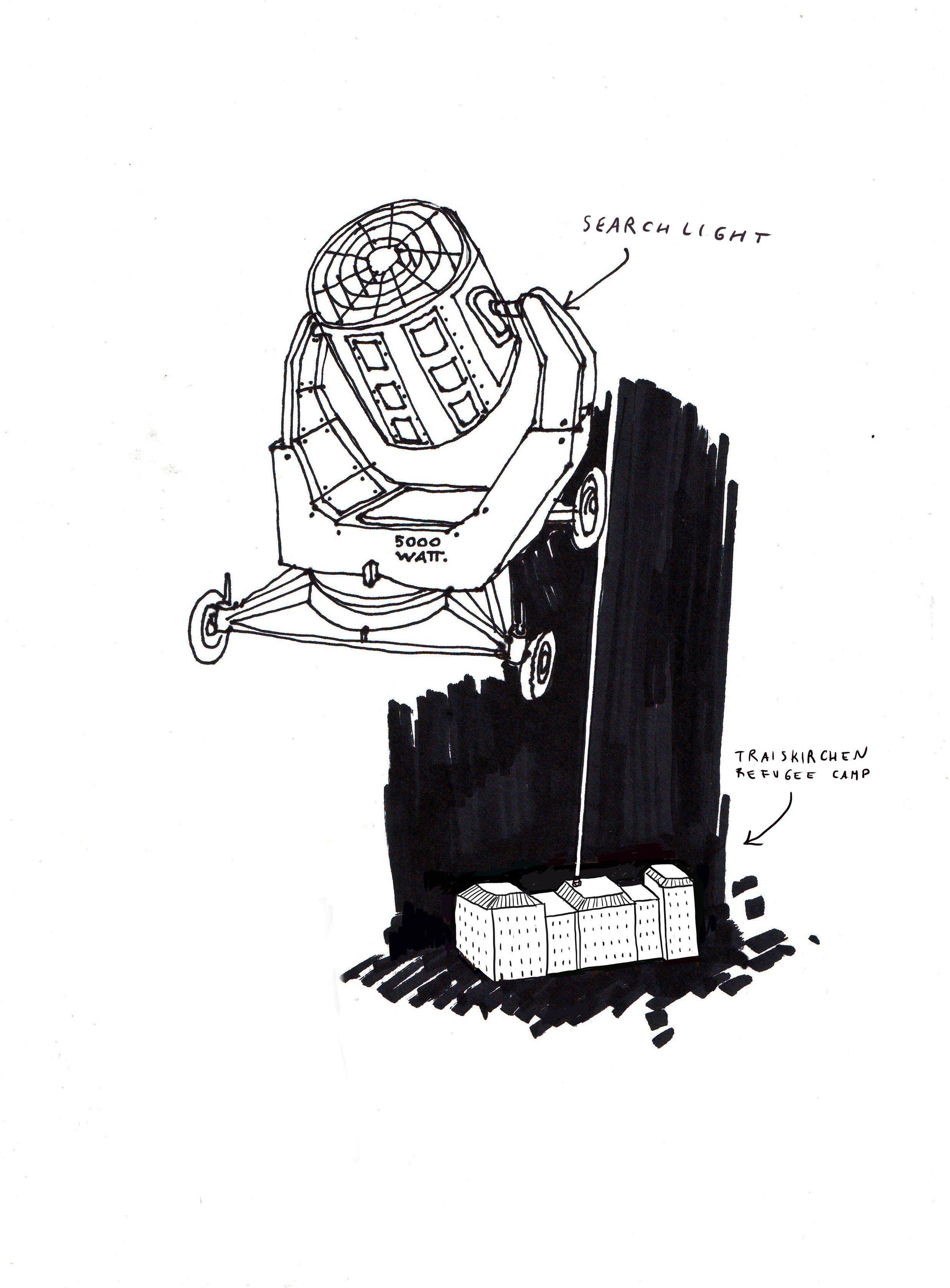

ALDO GIANNOTTI

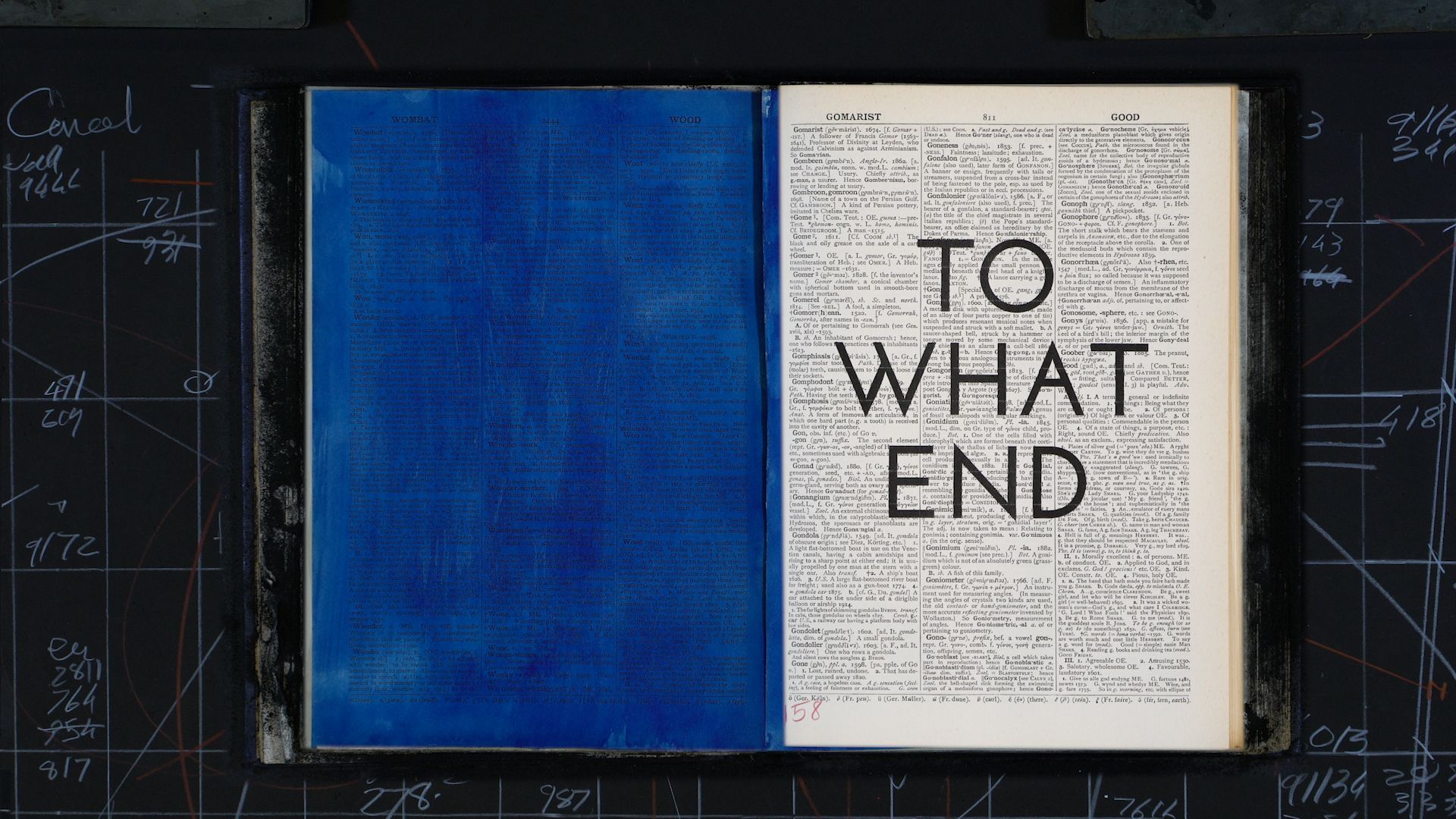

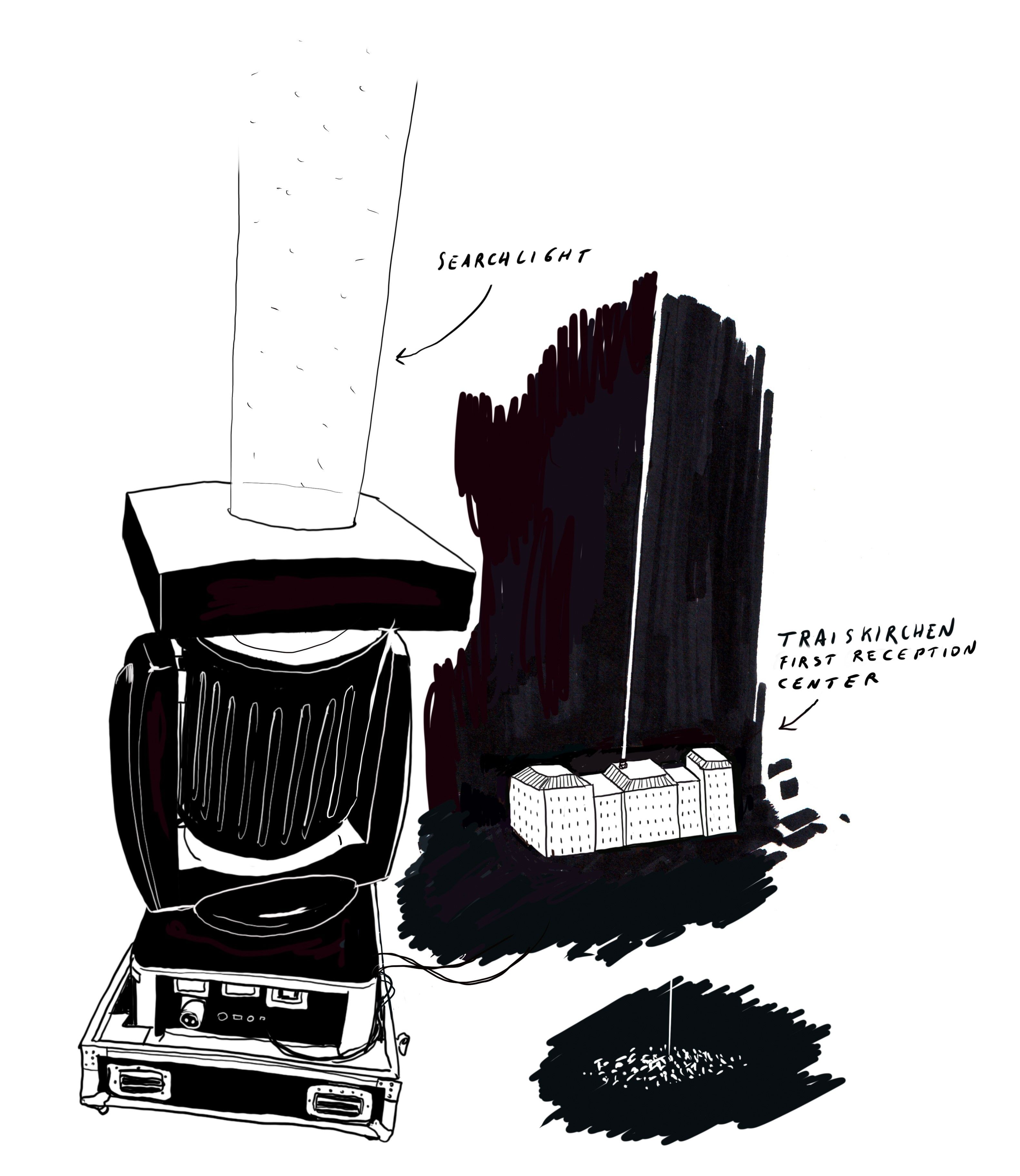

Searchlight

What does visibility mean in relation to its opposite: invisibility? Invisibility is not the same as absence. Light, on the other hand, can make something that is invisible or hidden visible or striking. The question that arises in this context is: What parts of society are in the dark and are for the most part invisible?

Aldo Giannotti places a simple mark, a point of light, in Traiskirchen near the reception center for refugees. It is a column of light that can be seen from afar that aims to raise the visibility of people who are in a situation that is all too often overlooked.

Anna Jermolajewa

Welt am Draht (World on the Wire), Postcard

Phone booths were once a central tool of communication, but today there are only a few of them left. Some have been transformed into book booths, others into little exhibition spaces, or EV charging stations. Today, phone booths are objects from are bygone era.

The majority of all international calls in Austria are made at the six phone booths on the grounds of the reception center. Anna Jermolaewa herself lived in the reception center in Traiskirchen as a political refugee from the former Soviet Union in 1989. In her work Welt am Draht (World on the Wire), the artist explores her own life story. During her time in Traiskirchen, she used these phones to talk to her family. At the time, they represented a connection to her life before she fled. Today, more than 30 years later, the phones have become a readymade that appear inconspicuous at first glance, but they also has a strongly symbolic value. Although they can be seen from the street, non-residents cannot look inside or use them, because the grounds of the reception center are strictly off-limits for visitors.

The postcards can be found at the City Hall and other locations around the city.

Anna Jermolajewa

Research for Sleeping Posittions, Video

After Anna Jermolaewa arrived in Vienna as a political refugee, she spent one week on a bench at the Westbahnhof train station in Vienna before she was moved into the reception center in Traiskirchen. In her work Research for Sleeping Positions, she refers to a situation that is familiar to many refugees. She tries to rest and sleep on a bench while in transit. The bench is extremely unsuited for this, and she constantly changes her position but cannot sleep. She demonstrates the impossibility of resting here, because the design of the seat is meant to make it impossible for certain groups of the population to stay there for a longer time and is thus intended to exclude them from the public realm.

Refugees have been arriving at the Westbahnhof train station for decades. When special trains with refugees arrived in 2015, many moved on, while others stayed in Austria, following Jermolaewa’s footsteps with the Badner Railway to the reception center in Traiskirchen.

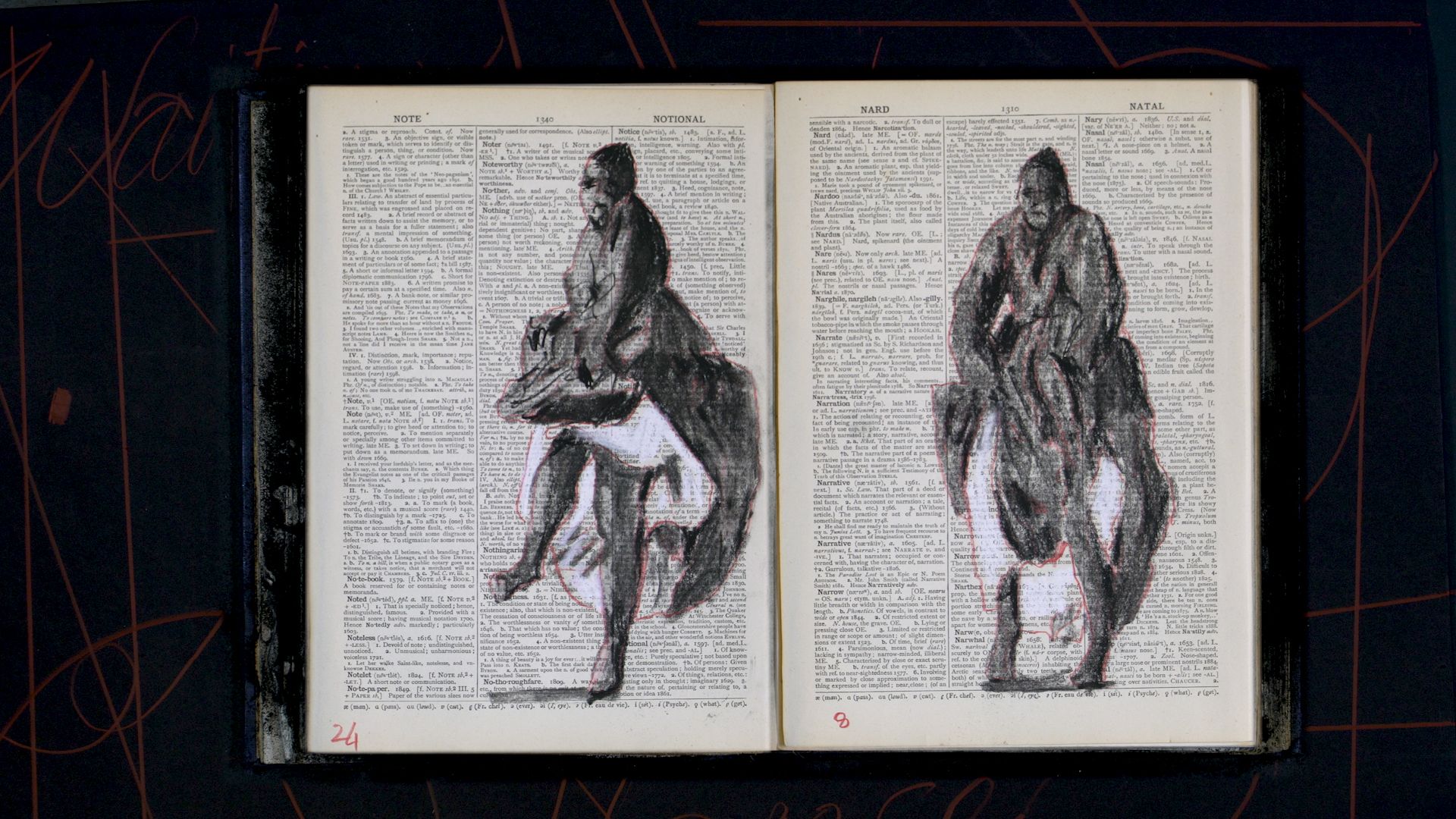

William Kentridge

Shadow Procession, 1999

Animated 35 mm film, transferred to video, 7 min

Processions are a recurring subject in William Kentridge’s work. In the video Shadow Procession, he creates a shadow play out of torn and cut pieces of paper. He places the figures on a transparent surface and photographs them, then changes their position and posture and photographs them again. The pictures have been edited into a movie in which a procession of figures and objects moves through the frame. A large figure appears that drives the procession with a whip. The people carry various objects, pushing or pulling their belongings through the picture. We cannot discern who they are or where they are going.

Director, animation, photography: William Kentridge

Music: Alfred Makgalemele

Editing: Catherine Meyburgh

Sound Design: Wilbert Schübel

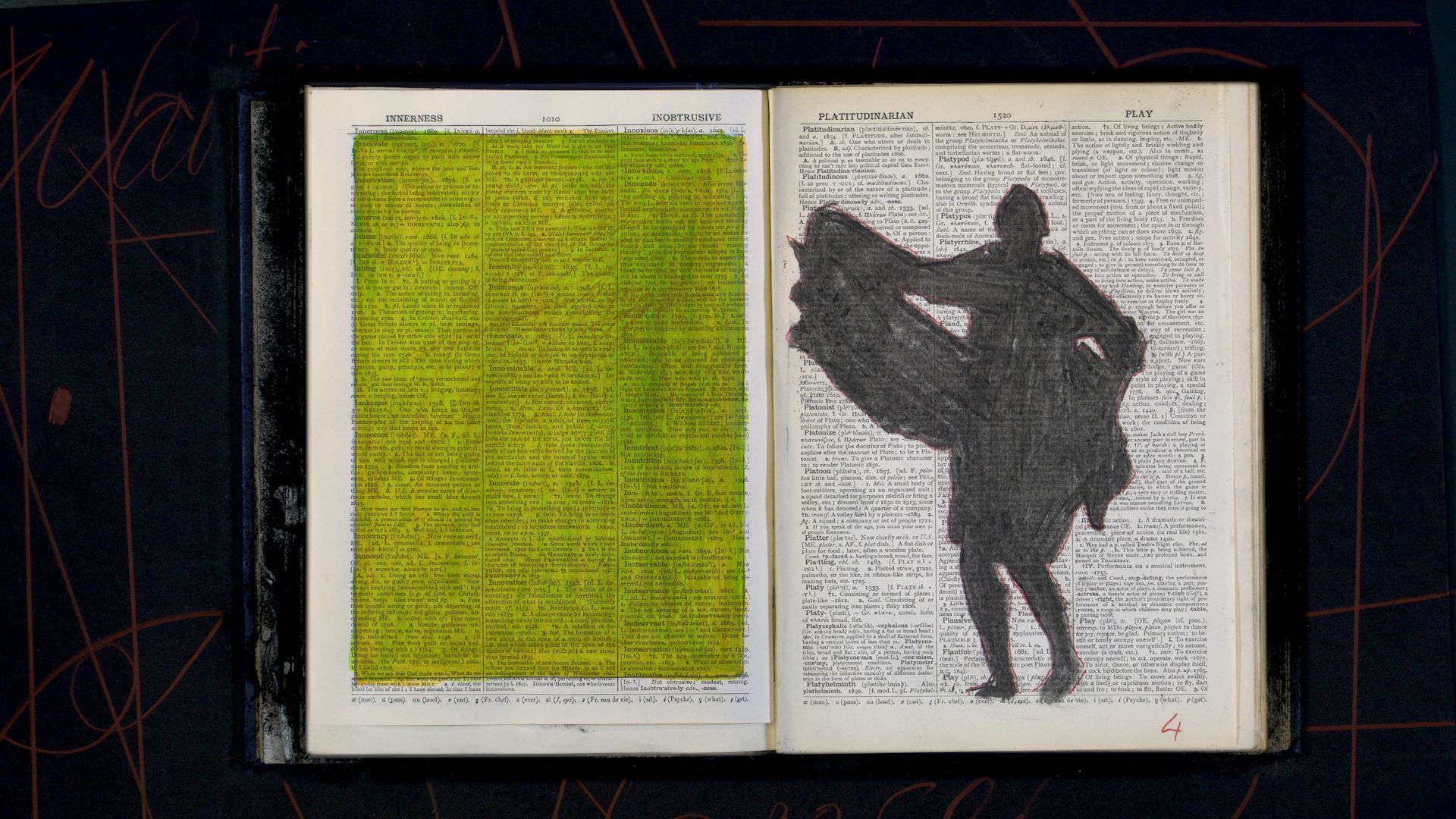

William Kentridge

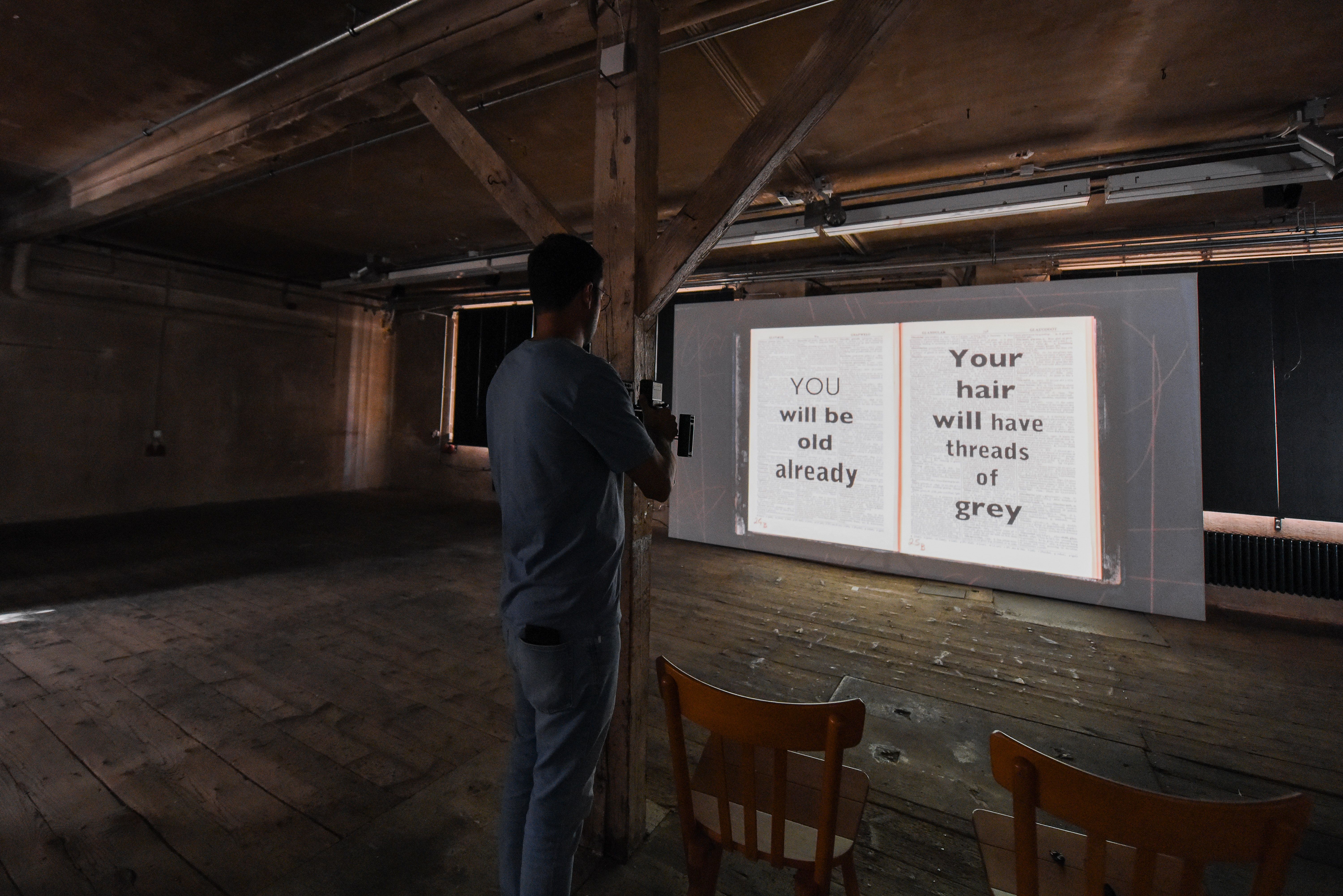

Sibyl, 2020, Flipbook film

Single-Channel Video, Color, Sound, 10 min

The video Sibyl tells the story of the mythological prophet Cumaean Sibyl, who wrote people’s fates on oak leaves and then placed these at the entrance of her cave. Her prophesies would be scattered by the wind, however, causing the fates of people to get mixed up. The people whose fate she was meant to predict never knew whether they were being told their own fate or that of someone else.

In this video, Kentridge shows these mystical and mysterious prophesies. He deconstructs individual fates and lets them merge into an enigmatic assemblage. The people’s future thus remains in the dark—similar to the future of the migrants and refugees who are in the midst of their asylum process. This time is often described as “the lost years.” This work addresses expectations as well as our unknown yet predetermined future that we cannot change through our actions.

Dariia Kuzmych

körperreich, samtig, stechend, pochend, (full-bodied, velvety, stabbing, throbbing)

Installation, textile, metal, measurements: 8 x 3.5 m

The perception of time is subjective. We always see it in relation to the things we do or experience. It can fly by, or it can seem to stand still.

It is said that wine is flowing time: the decades in which grapevines collect minerals from the soil, the time the grapes ripen under the sun, and the time needed for their cultivation and harvest. Traiskirchen as a city of winegrowing is one of the starting points for Dariia Kuzmych’s work. Wine is pleasure, something that, when consumed in moderation, is associated with a nice way to spend time.

Against this backdrop, Kuzmych’s work juxtaposes two entirely different temporalities: the perception of time in connection with wine and pleasure, and the perception of time when experiencing traumatic events. In crisis situations, time becomes fragmented, and daily routines are disrupted. In the midst of this disjointedness, the qualities of time are distorted. Time stretches and freezes in the moment of the rift. This experience is inscribed on the personal and collective memory of time, like on a plant.

The installation, which looks like a sun screen, is overlaid with swaths of fabric with flowing, abstract representations of time and with cut-outs that let us see through it in places. The different perceptions of time when experiencing enjoyment or pain meet each other to become a tangle of situations and moments in life.

The project was realized with the support of Svitlana Selezneva, Stephka Klaura (FabrikFabric), and the Academy of Fine Arts.

Alicja Rogalska

Alterations

Textile collage, used clothing and fabric, measurements: 7 x 5 m

In collaboration with Zahra Akbari, Bashirahmad Hasanzadeh, Roya Nasrati, Obaidullah Shirzad, Paulina Semkowicz, and Margot Handler

The recognition of foreign job qualifications and university degrees in Austria is more than just a challenge for many refugees. Often, people can no longer work in the occupation they were trained for in their home countries because European authorities require an equal level of education.

Refugee tailors have been working in the sewing workshop of the Garten der Begegnung (a communal project for refugees and locals) since 2017. They alter and customize clothing and sew new clothes. A majority of the people working in the workshop cannot work in Austria in the job they were trained for in their home countries.

In collaboration with a group of refugee tailors from the sewing workshop, Rogalska created a large textile picture out of donated clothes. The project was also accompanied by a lawyer specializing in labor law and the recognition of foreign job qualifications. He researched legal methods of interpretation and possibilities for recognition. Just like how clothes must be altered occasionally to suit a different or changing body, the existing legal system is not static, but is a flexible complex that is also regularly altered.

The creation of the textile work was documented by Moka Sheung Yan (photography) and Sobhi Aksh (video).

With support from the sewing workshop of the Garten der Begegnung association, and from carla Vienna, Vinzi Shop Ottakring, Ann Cotten, Leonard Ellis Clarke, Alyona Kovalyova, Dariia Kuzmych, and Anna Witt

Kamen Stoyanov

Ein Realist oder ein Träumer (A Realist or a Dreamer), Video installation

Video, duration; installation, various materials

With Hatam Hemmati Sherkab

Seeds are sown in the garden, the ground is tilled, plants are planted, flower beds are made, and weeds removed. This is meditative work that requires physical effort. Each year, the Garten der Begegnung is cultivated and prepared for harvest. It is tended by the citizens of Traiskirchen and refugees together.

For this video, Kamen Stoyanov accompanied a former resident of the refugee reception center in Traiskirchen at work in the Garten der Begegnung and at home in supported housing. His hopes and fears are directed toward the future. His work in the garden begins to blend with his vision of the future, with its hopes, opportunities, dreams, and nightmares.

Rayyane Tabet

Steel Rings (2013 – ongoing)

Installation, 20 steel rings, 80 x 10 x 0.6 cm

The Trans-Arabian Pipeline Company (TAPline) was founded in 1946. The company built a 1,213-kilometer-long pipeline that transported oil over land from Saudi Arabia to the Mediterranean Sea. During its entire lifespan, the TAPline was witness to the socioeconomic and geopolitical crises in the Middle East: the Exodus of the Palestinians in 1948, the Suez crisis in 1956, the Six-Day War in 1967, and the Yom Kippur War in 1973. All of these events contributed directly or indirectly to the company’s rise and decline. The company collapsed in 1982. To this day, the Trans-Arabian Pipeline is the only physical object that crosses the borders between Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Syria, the Golan Heights, and Lebanon.

Steel Rings is a sculpture that reproduces segments of this now retired pipeline. Each segment has the same diameter and is made of the same material as the original pipeline. Each ring represents a kilometer of the original and is marked with the latitude and longitude of the original location. In Traiskirchen, Tabet is presenting a segment about twenty meters long from the Golan Heights.

Anna Witt

Routineübung (Routine Exercise)

Performative interventions and video

The Theater of the Oppressed is a political form of theater that was developed by the Brazilian director and theater theorist Augusto Boal in the 1970s. It is based on the idea that theater can be a political instrument of protest capable of showing social alternatives, while also turning hierarchal rules upside-down. It suggests methods of utilizing processes of development and change.

Together with Traiskirchen locals and refugees, Anna Witt has developed performative scenes based on Boal’s theater experiments that are grounded in actual situations that have been fleshed out and fictionalized. They imagine possible ways to act out of solidarity and moral courage. Like exercises that are done to prepare for emergencies, routine movements were developed that could be applied as playful exceptional situations in public places.

The interventions, which were documented with infrared cameras, can be seen in a control station that is similar to a surveillance room.

With support from InfraTec GmbH

Images (35)